The Schvitz: Detroit’s Historic Bathhouse Reborn as a Modern Wellness Haven

By Cashmere Morley • Photos by Susan Ayer

On the edge of Detroit’s North End, on the corner of Melbourne Street and Oakland Avenue, is a hulking gray building. Cars steadily line the otherwise empty surrounding streets. People spill out of the unmarked building, sometimes in robes or bathing suits. Laughter and conversation bubbles from the patrons, steam rising off their bodies if it’s cold outside or sticking to their skin if it’s hot. The building is pockmarked with clouded windows, giving no visual cues as to what’s inside. The neighborhood the building sits in, once dense with working-class Jewish families, Eastern European immigrants, and factory workers drawn by the hum of the city’s industrial heart, is now dotted with old warehouses.

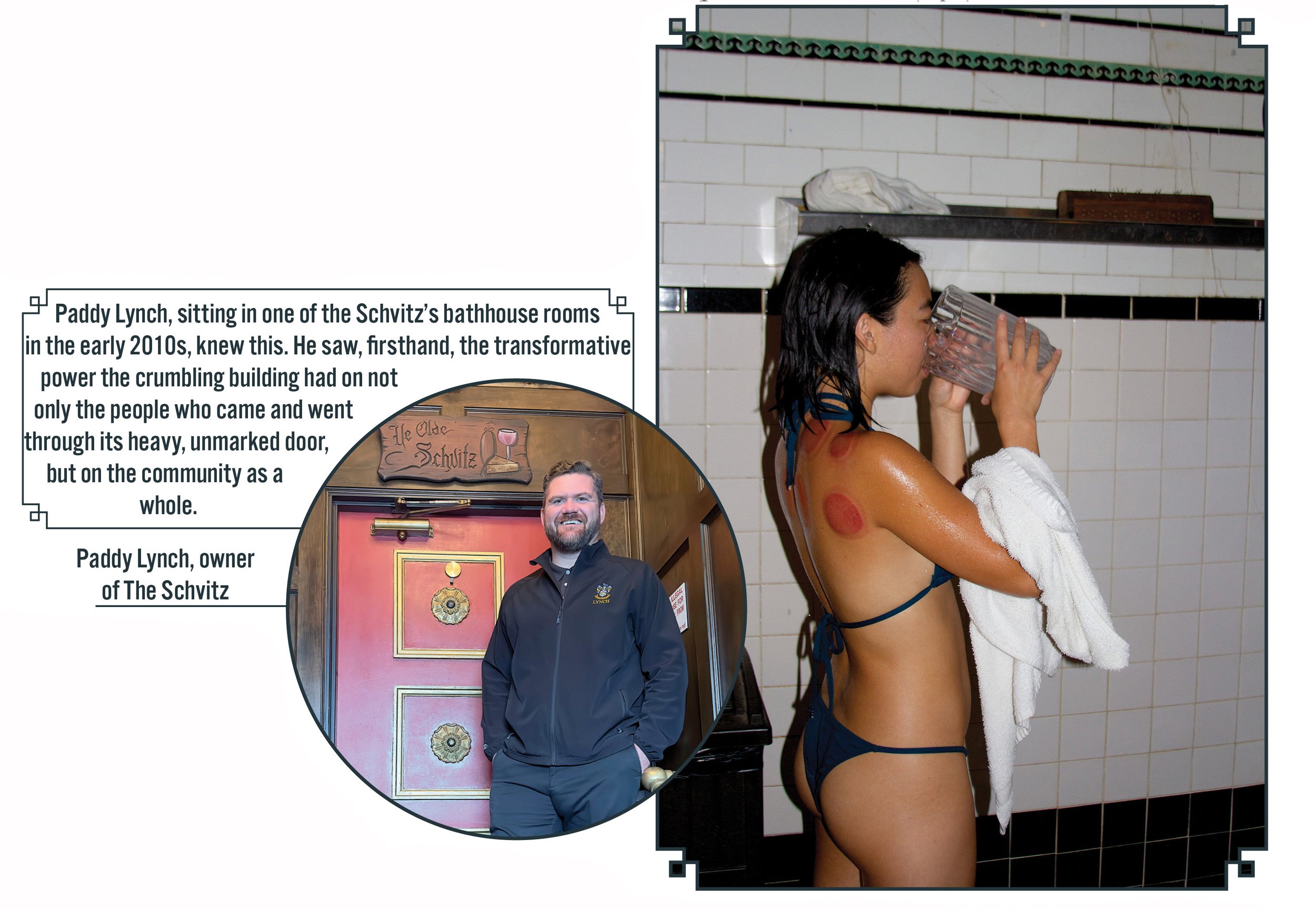

Once central to Detroit’s auto manufacturing boom, these buildings are weathered but still standing. To the well-aware, the gray building acts as a mirror to its surroundings offering reprieve to the weathered but still standing Detroit scene since 1930. The building was never part of the manufacturing boom, at least not in the same way, but it housed and healed many people who were. Paddy Lynch, sitting in one of the Schvitz’s bathhouse rooms in the early 2010s, knew this. He saw, firsthand, the transformative power the crumbling building had on not only the people who came and went through its heavy, unmarked door, but on the community as a whole. When the building quietly went up for sale in 2017, the third-generation funeral director, and avid house restoration contractor, knew he could breathe life into the dying bathhouse. But the story of how Lynch transitioned from funeral director to funeral director/bathhouse owner requires a bit more explanation.

“I bought a house in Detroit 14 years ago,” Lynch began, “And at the time, my friend, photographer Ara Howrani, encouraged me to go into the Schvitz when we were driving around the neighborhood one day. I didn’t know anything about it, other than it’s seedy, sketchy reputation at the time as a swinger’s club on the weekends,” Lynch laughed. “And then finally, one night, this has got to be at least 12 years ago, we went in. We went down this long hallway. The place was, like, really dingy and kind of run down, but we came upon a table full of old Jewish and Russian dudes eating steaks in their robes and drinking vodka and smoking joints. And we were like, oh my god, this is unbelievable.

They were actually really nice. We told them who we were, and that we lived in the neighborhood, and we were just there to check it out. And ever since that first encounter, I just started going back once a week as a funeral director. I was… well, I guess I still am, but especially then in my late 20s, I was just really stressed, trying to figure out where to find some peace and quiet and sort of a break from the sadness of the work. And I found myself going to the Schvitz once a week and just loving the fact that I could lock my phone away and just detach for like, two or three hours.”

The Schvitz, Yiddish for “sweat,” has long been a space for physical and spiritual renewal. Originally frequented by Detroit’s Eastern European Jewish population, and later owned by gangsters, it served as a vital community center where men gathered to detoxify, socialize, and find respite from their daily lives.

“At the height of prohibition, the Meltzer family, who was loosely affiliated with the Purple Gang, the Russian Jewish mafia of Detroit, took control of the building, and they’re the ones that established it as the Oakland Avenue Bathhouse. They loved it, and wanted it for religious and cultural reasons, but also for business reasons. When you’re in a 220-degree room, you can’t wear a weapon or a wire, and so that’s where they had their confidential conversations.” said Lynch. “After Prohibition, it was racketeering, high stakes gambling, hookers. I mean, it had everything. But at the same time, it always attracted rabbis and businessmen and bureaucrats and it always kind of had this fascinating duality, where… if there was sinning, it was sort of sinning privately, but it was always also open to the public.”

The public, meaning, at the time, only men. “Well… old grandma Meltzer, who ran the kitchen, she’d kick all the gangsters out once a week and let all the women in from the community, which I think is awesome,” Lynch added. But beyond the occasional charitable Yiddish grandmother, the Schvitz remained a men’s only club until Lynch bought the bathhouse in 2017. “There was always a thread of femininity there. It just wasn’t fostered and celebrated until we took over. I’m super proud of it, but it’s also been a team effort.”

Over the years, the bathhouse’s clientele diversified, but its core purpose of offering sanctuary remained unchanged. The 1930s were a time when communal bathhouses were as much a part of daily life as corner delis and union halls. The men who came here in the early days—factory workers from the auto plants, newly arrived immigrants, butchers, tailors, bricklayers—spent their days toiling in unforgiving conditions. Their bodies ached, their lungs burned, their bones settled into the dense weight of industrial life. The Schvitz was where they came to burn it all off. They’d strip down, sweat out the soot and strain, and emerge—however briefly—lighter.

The idea to diversify the bathhouse came to Lynch when one day, Lynch’s sister, an opera singer, invited him to New York to watch her perform. Knowing he frequented the Schvitz, she asked her brother if he had ever been to the Russian and Turkish baths in the famous East Village. “The Schvitz is a dump,” she told him, “You need to check out this famous place in New York.” And it was there that Lynch’s “eyes opened.”

“It was young, it was old, it was white, it was black, it was male, it was female, it was all these things,” said Lynch. “And I was like maybe the Schvitz in Detroit could be bustling again like it was 100 years ago. And so, I called this old Soviet caretaker who’s still with me. He’s 78 years old. He never owned the building, but he had been taking care of it for, you know, at that point, 40 years, and he was sort of in charge of figuring out who the next owner would be, because this old widow owned it and never really had anything to do with it. She sort of inherited it, and it was uninsured and in disrepair, and it wasn’t listed for sale, but it was quietly for sale. And so, Daniel [the Soviet caretaker] sort of brokered the deal for me, and then I bought it in 2017. It’ll be eight years next month [that I’ve owned the Schvitz]. It was March 17 that I bought it.”

Inspired by his experience in New York, Lynch saw an opportunity to bring a new generation of people into the Schvitz, preserving its heritage while expanding its reach. His journey of restoration and community-building has not only saved the Schvitz from disrepair but has also turned it into a thriving hub that now welcomes over 300 visitors on busy days. A $40 entry fee guarantees you access to the health club for as long as you desire.

His first major change was introducing women-only hours, a shift that instantly broadened the bathhouse’s appeal. Before this, the space primarily attracted around 25 men on busy nights; with the introduction of women-only hours, attendance soared, eventually reaching upwards of 125 to 300 people during peak evenings.

“And that, in some ways, probably became the backbone of the business; when I bought it and told Daniel, ‘Hey, man, I’m sorry, but one of the first things we’re gonna have to do is cancel swinger night, because it’s only one night a week, but it’s probably keeping way more people away than it’s attracting.’ And no judgment. I always tell people like, ‘Hey, God bless the swingers, they help keep the lights on.’ It’s just that we’re in the middle of a full restoration. Keeping swingers night wasn’t gonna be in the cards. Daniel was extremely nervous about that. He was like, ‘You’re cutting the little revenue that this place has.’ And I was like, ‘you know, basically, have faith, we’ll figure it out.’ One of the things that we did immediately is establish women-only hours on a weekly basis.”

The building’s interior still feels carved out of time. The walls are thick with decades of condensed steam. The original tilework, some cracked and faded, still clings to the floors and walls like a mosaic of the different lives it’s seen. The wood-paneled sauna, large enough to fit a small congregation, has turned deep shades of brown from nearly a century of heat. The communal cold plunge pool— fed by icy water—has shocked generations of bodies back to life for decades.

Detroit itself has changed dramatically around The Schvitz. In the decades after it was built, the city soared—its auto industry powering the country, its neighborhoods dense with families, its streets alive with the hum of industry. Then came the unraveling. Factories closed. Families moved. Entire blocks were left to rot. But The Schvitz remained. Even as the neighborhood around it hollowed out, the bathhouse endured—a stubborn ember of heat and community in a city gone cold.

Today, the North End is stirring back to life. Artists, small businesses, and longtime Detroiters alike are reimagining what the neighborhood can be, and The Schvitz is a part of that reimagining. It is a place that belongs, in a profound way, to Detroit’s bones—a space where the city’s past, present, and future blur in the steam rooms.

And this, Lynch understands deeply. He understands that buildings like the Schvitz are rare—not because of their grandeur, but because of their persistence. In a city that has been written off, rebuilt, abandoned, and reclaimed time and time again, the Schvitz has simply stayed. It has absorbed the weight of the city’s history and kept burning. And now, under Lynch’s care, it has once again become a central Detroit hub—a place where bodies can unburden themselves, where the heat works like prayer, and where the city, in some small but essential way, heals itself.

There is something to be said for a person that deals with both the living and the dead. Both spaces serve as thresholds between two states of being. In a funeral home, one guides people through the transition from life to death, offering solace, ritual, and closure. In a bathhouse, one facilitates a transition from tension to relaxation, offering renewal, healing, and restoration. Both spaces strip away pretense—in the funeral home, death reduces everyone to their most vulnerable state; in the bathhouse, nudity and sweat dissolve social hierarchies. But both, in their own way, are about care for the human form.

Lynch’s role in both spaces speaks to a deep, perhaps unconscious, calling to serve people at their most human moments—when they are stripped of artifice, either in death or in the vulnerable act of sweating and cleansing. In a way, both spaces offer rituals of passage—one for the soul and one for the body. Without necessarily intending to, Lynch has found himself shepherding people through transformation—helping them let go of something old (whether it’s tension, grief, or life itself) so that something new (peace, community, or renewal) can emerge.

The energy of the bathhouse, while fueling a space for forward, intergenerational human connection, also feels rooted in the past in a way that is hard to communicate. The lives and conversations of many bathhouse-goers hang in the air as thick as the steam. “The Schvitz is an equalizer,” Lynch said, noting how people from vastly different backgrounds come together here.

“What’s really interesting is that people always think, ‘oh, you’re a funeral director. The funeral home has to be more haunted than the old bathhouse’. What I’ve learned anyway, from people who consider themselves experts in that field, is that the dead would really want to haunt where they spent a lot of time alive, and people don’t spend a lot of time in a funeral home. But they hang out here every week to relax. I had one young woman I know, sort of a local clairvoyant legend in Detroit come through, and she was like, ‘the Schvitz is just absolutely packed with spirits.’ And most of it being benevolent people that just want to be there. But yeah, they said the energy is incredibly thick.”

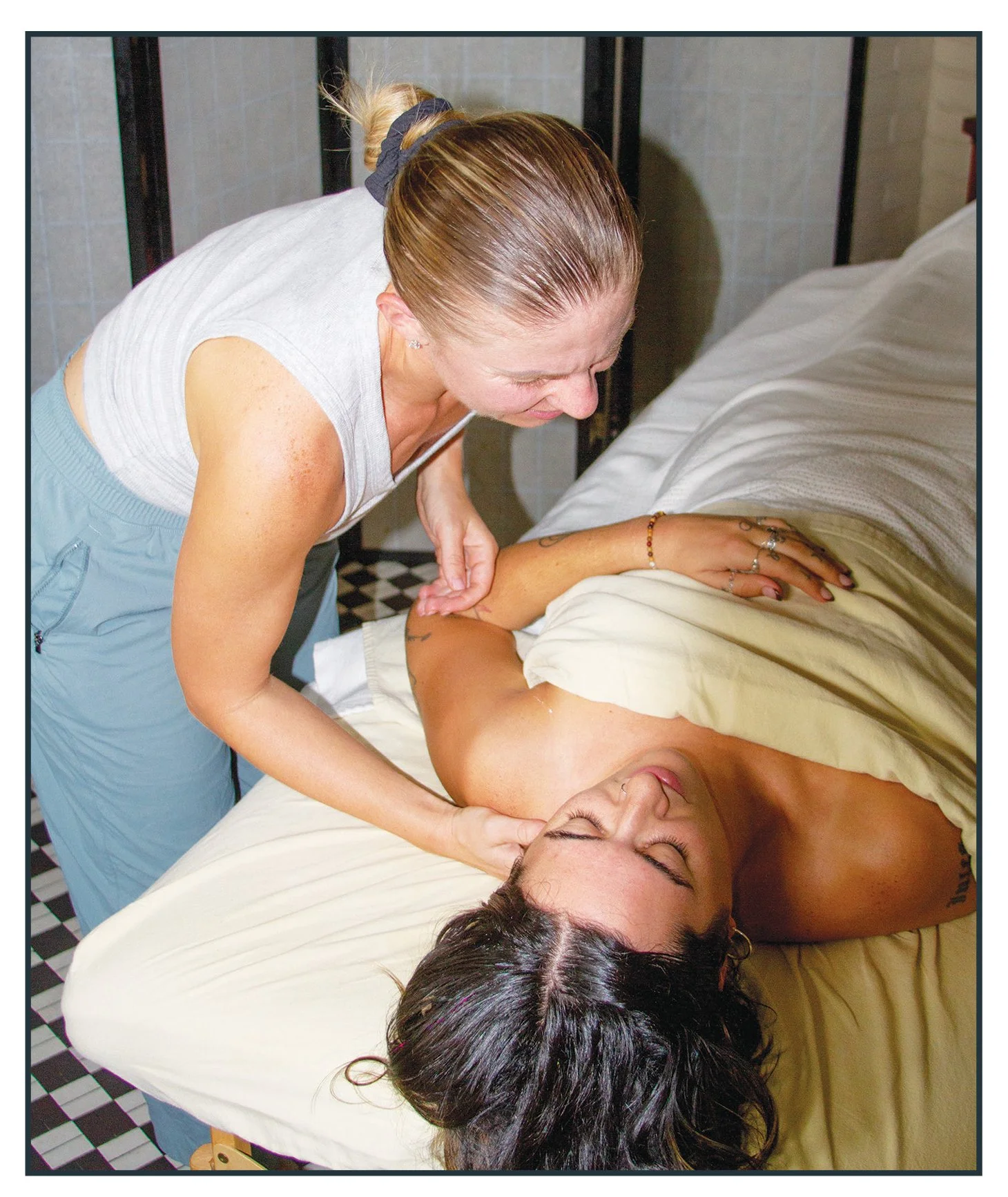

Lynch’s commitment to inclusivity and accessibility turned the Schvitz into more than just a bathhouse: it became a gathering place where people from all walks of life could connect, unwind, and rejuvenate. Today, the Schvitz operates seven days a week, offering a range of services including sauna sessions, massages, steam baths, and cold plunges, all of which have been celebrated for their health benefits such as improved cardiovascular health, reduced anxiety, and enhanced overall well-being.

Initially a venue for pop-up food events, the Schvitz has since evolved into a full-service dining destination featuring a consistent traditional menu. The transition was driven by increasing demand from Schvitz patrons who craved a space to continue their conversations and experiences after their sauna sessions. Today, visitors can enjoy everything from Eastern European comfort food to inventive modern dishes, creating a seamless connection between the old and the new.

The resurgence of interest in communal bathing spaces has further fueled the Schvitz’s popularity. In a world increasingly driven by digital interactions, the physicality of the Schvitz experience offers something rare and profound: genuine human connection.

As the Schvitz continues to thrive, Lynch and his team are already looking toward the future. Plans are in place to expand the Schvitz’s reach by opening satellite locations in other cities, allowing more people to experience the magic of communal bathing. Additionally, there are discussions about expanding hospitality services at the Schvitz, including the possibility of overnight accommodations for visitors seeking a full immersive experience—look at the Little Schvitz and the North Schvitz locations for more information. Their ballroom is also in full renovation with the hopes to host parties and weddings in the near future.

Beyond physical expansion, Lynch remains deeply committed to preserving Schvitz’s core values of community, inclusivity, and wellness. He envisions a future where the Schvitz serves as a model for how historic spaces can be reimagined and repurposed without losing their essence.

The Schvitz’s story is ultimately one of restoration—not just of a building, but of a tradition, a community, and a shared human experience. It stands as a reminder that even in a rapidly changing world, some things—like the healing power of steam, the warmth of community, and the importance of human connection—remain timeless.

Visit The Schvitz online at schvitzdetroit.com, or on Facebook @schvitzdetroit and Instagram @theschvitz. Check online for women’s hours, men’s hours, and all-gender hours.

It came over me one morning. I dressed, and undressed, and redressed several times. Shirts and pants I had worn many times suddenly made me feel claustrophobic. The colors were good, the styles attractive. This wasn’t a “what do I want to wear?” indecisive moment. No, it was as if every shirt and pair of pants I tried, I felt like my skin couldn’t breathe—that I couldn’t breathe (and not because I had strawberry shortcake with morning coffee). I pulled at the necklines, the thighs, the abdomen. I fidgeted. I could feel confused grumpiness setting in.