Letting Go of Defenses After Decades

By Amy Lagler

A few days ago, my boyfriend told me to “toughen up.” He was joking, but it still made me smile. Really, it made me feel successful, as I’ve been heading in the other direction for a while now, searching for the softer, more vulnerable side of myself. It’s taken me decades to get here, to push past my fears and pull down my own defenses from the inside. I’d built myself a pretty impressive fortress.

I grew up in the seventies, an era of empowerment for women and living in a college town, I was raised on the heady promises that I was just as good as the boys and could be and do anything I wanted—nothing was out of my reach. But, like now, the path was a dangerous one and the threats mostly came in the form of men.

To be fair, the first person to beat me up was my friend Nancy. It was third grade, and I certainly had it coming, but it was the first time anyone had hit me. It’s sad to me that I look at that statement now and think how lucky I was. I made it to third grade without anyone striking me! I didn’t even know what to do, except go home and tell my mom I got beat up. She was a little alarmed that I hadn’t even tried to defend myself. It wasn’t the first time she wondered whether there was something wrong with me (I didn’t learn to tie my shoes until second grade) and she told me, in no uncertain terms, that I should always defend myself, that I should never allow someone to hit me. It was great advice, and I took it to heart.

The problem, of course, was that the ensuing years were full of threats of violence, and I learned the best way to respond was with more violence, often preemptive violence. If it appeared that I was turning the other cheek it was only because I was setting my stance and winding up. In junior high, I became a bit of an enforcer, avenging myself and my girlfriends when the boys tried to hurt us. I wouldn’t develop my verbal abuse skills until later (I was still too shy), so my fists and my feet were my weapons of choice. I’d been a scrawny kid, but by high school I was 140 pounds of muscle, and I needed every pound of it. High school was brutal.

My particular high school had a common area that you had to pass through to get anywhere (who thought that was a good idea?). The upperclassmen would hang out on “the rail” at the entrance to the commons and hurl commentary and insults at the girls as they passed by. I had older sisters so was already aware of some weak spots and potential lines of attack that I needed to defend, mostly centered on my maiden name, which was easily converted into a sexual slur.

The very first time I walked through the commons as a totally terrified freshman, a boy stepped away from the rail, blocked my path, and called me the slur. Thankfully, he was on the small side so when I hauled off and decked him with a right hook to his face he went down. Then, I stepped over his body and went to class. No one ever called me that name again. I went on to develop a number of reputations in high school but that first one, the “don’t mess with her” one, lingered and I was grateful for it.

Over time though, the boys got bigger and I got smaller, so I learned to rely on my words more than my fists when I needed to attack. Eventually, I got really good at verbal abuse and could typically eviscerate anyone in three sentences or less. It didn’t necessarily make me popular, but it made me feel powerful and protected. Needless to say, I never cried. If I felt scared or wounded, I lashed out—an unfortunate life skill I relied on for a long time as the world didn’t become a less threatening place when I got out of high school. In the following years, I had to fend off men who were far more powerful than me—a professor, a state senator, a giant biker in a blues bar. I liked men, a lot, but I didn’t trust them at all. Then I met my husband, who was trustworthy and gentle in every way.

We were married 28 years, an experience which taught me a lot about building and keeping a loving relationship going. Rule #1: don’t ever, ever be mean to one another, even when you are really, really, annoyed. Of course, that didn’t translate into me never being mean to others. I remained capable of some serious verbal brutality when provoked. I also remained doggedly independent, refusing to let my husband run any kind of interference when other men insulted me or challenged me. He learned to step out of my way so I could fight for myself.

In the end, the fortress I was defending proved a sorry bulwark against the really threatening stuff, like illness and dying—and I learned to cry. Well, it wasn’t really a learning thing. I guess I’ll say I started to cry. I’m still not a fan of bursting into tears, but it’s something that happens now whether I like it or not. In truth, living in a fortress was exhausting, and trying to protect myself from the meanness of others by being even meaner had taken a huge toll on me. It also made me sad, and I had enough to be sad about already, so I decided to drop my defenses—to put it all down—to refuse to be provoked.

Anyone who has ever tried to rid themselves of a bad habit or pattern of behavior knows that it wasn’t that simple. I liken it to trying to get your dog to put down some nasty thing they’ve picked up in their mouth along the way. It usually involves a lot of yelling “Drop it!” or “Put that Down!” at increasingly more insistent volumes. For years now, I have been yelling “drop it” to my train of thought whenever it veers off to pick up a snarky stick in order to pummel some jerk.

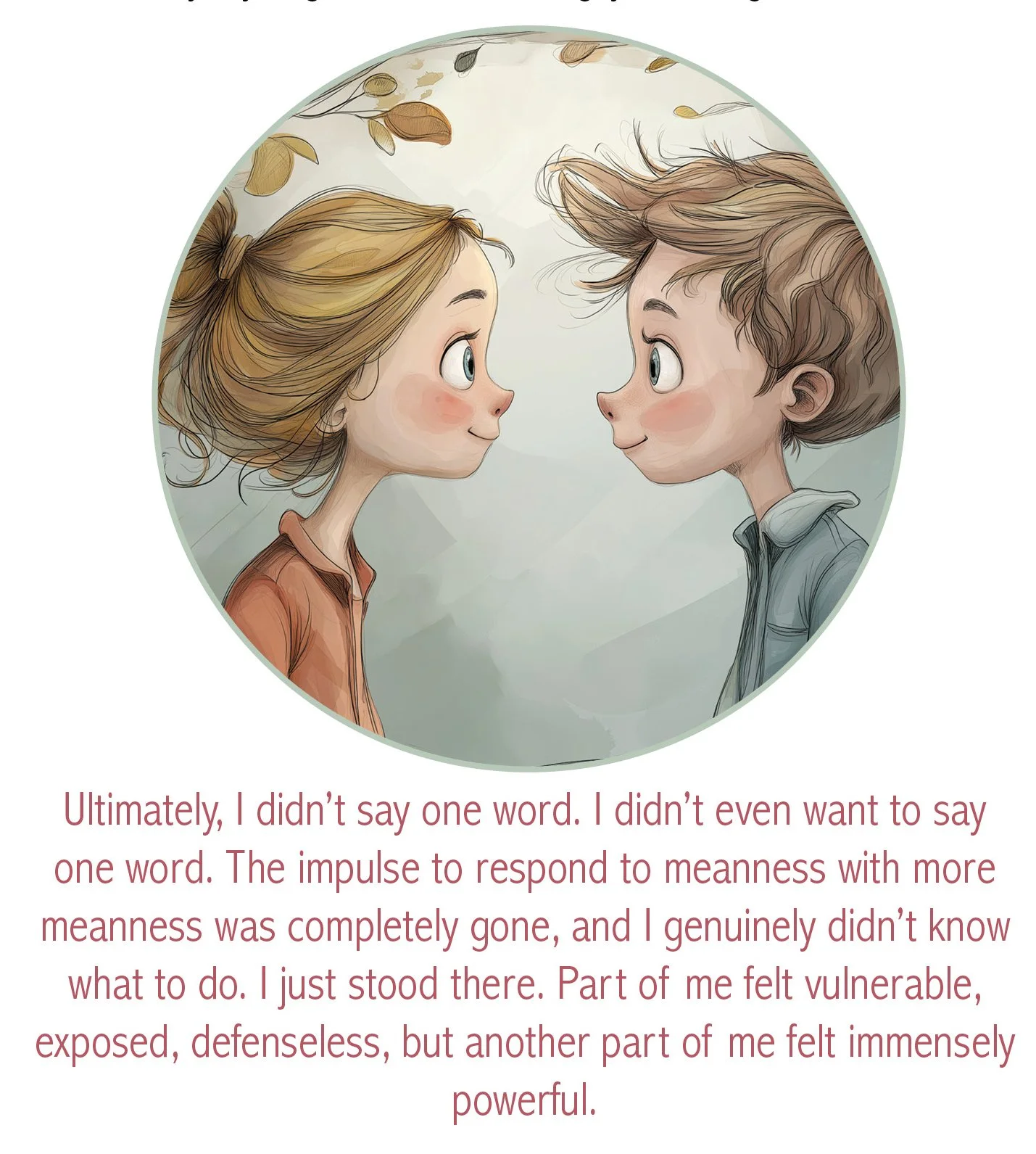

It was going pretty well until, inevitably, I found myself in a situation where a snarky stick would have come in handy. I was in a sailing class, trying to learn how to rig a Hobi Cat. I had volunteered to be the first to learn how to raise the sail, but when I stepped up, in front of a dozen other students, the male teacher said, “You know what, why don’t you just figure it out on your own?” I have no idea what his problem was, but when I looked at him, I recognized the expression I’ve seen so many times in my life—the mean, little, self-satisfied smirk of someone who’s set you up to fail, or be publicly embarrassed, or (in this case), both. In the past I would have humiliated him right back with a few choice, vicious words. But in that moment, I just stood there, looking at the rigging, his smirk, and the sympathetic faces of the other students, who didn’t need me to say anything to understand this guy was being an ass.

Ultimately, I didn’t say one word. I didn’t even want to say one word. The impulse to respond to meanness with more meanness was completely gone, and I genuinely didn’t know what to do. I just stood there. Part of me felt vulnerable, exposed, defenseless, but another part of me felt immensely powerful. It’s the power you feel when you finally get yourself under control and let go of an old, impulsive pattern that is harming you. In this case, it was the power of realizing that other people’s bad behavior no longer provoked me. It felt great. At some point, my boyfriend (a skilled sailor) stepped up and calmly showed me how to rig the boat. I don’t know how the teacher took that as I had stopped paying attention to him completely. I hope he got a little schooling of his own, in what it is to be a kind man. I should say a kind human being as, obviously, it’s a lesson it took me a long time to learn myself.

In the end, I’m still not sure about this crying thing (really? right now? over that?) but if it’s the cost of living outside the fortress and putting down all my sticks, it’s a price I’m grateful to pay.

Amy Lagler lives in Ann Arbor. She never did learn to sail but the nice boyfriend is still around. Lagler can be reached at habitualtimewaster@gmail.com.

A decade after falling in love with Hamilton's "Look around, look around at how lucky we are to be alive right now," this personal reflection explores shifting from optimism to unease in turbulent times. Drawing on Eliza's line—"Look at where you are, look at where you started. The fact that you’re alive is a miracle"—and Niall Williams' This Is Happiness, it affirms our role in carrying the past into the future with gratitude and perseverance.