By Kirsten Mowrey • Photos by Edda Pacifico

Language is the lens through which we express our internal experience of the world and build relationships outside ourselves. For centuries, the Great Lakes watershed and Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) danced this give and take, Land shaping language, language mirrored to Land, until ruptured by colonization.

Twenty years ago, Stacie Sheldon and Margaret Noodin founded the website ojibwe.net in Ann Arbor, beginning the hard work of revitalizing Anishinaabemowin language, speakers, and culture. Their work is part of greater regional shift, which in 2025 saw Detroit’s first pow wow in thirty years, a major exhibit open at the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the arrival of Ann Arbor District Library’s mascot, Akako G. Shins (“little groundhog” in Ojibwe).

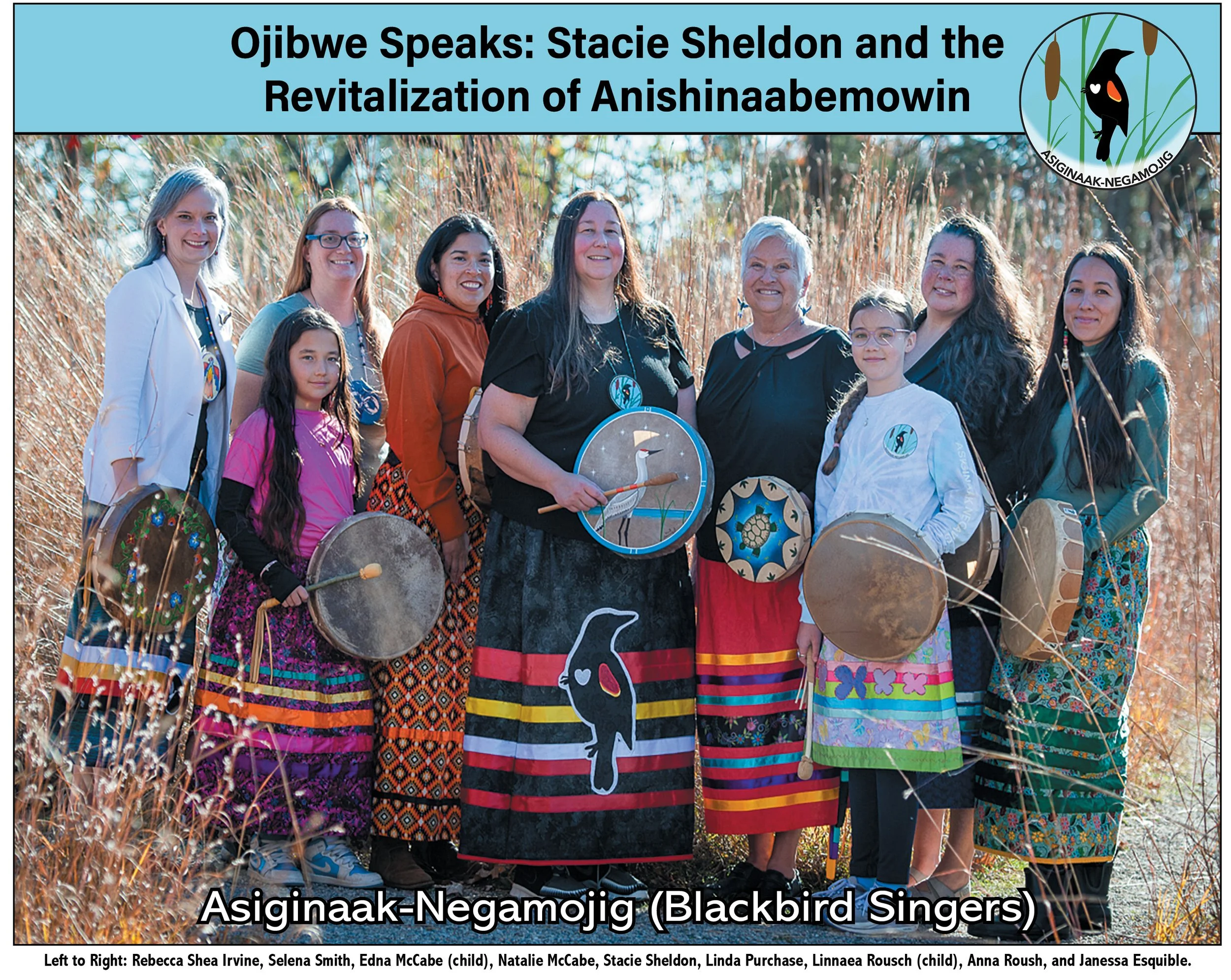

I spoke with Stacie in September, the day before her women’s singing group, Asiginaak-Negamojig (the Blackbird Singers) performed the welcome song opening the exhibit at the DIA.

Kirsten Mowrey: Where did you spend your childhood? When you were growing up and in college, what was your relationship to the Anishinaabe language?

Stacie Sheldon: I grew up in Cheboygan, Michigan which is on the eastern side of the tip of the lower Peninsula, about 15 miles south of Mackinaw City. I went to Michigan State. I studied literature and literary theory, border identity—Mexican and American.

I didn't have a relationship with Anishinaabe language until 2006 or so. I was 15 when the Native American Languages Act was passed in 1990. There was not any language stuff happening in northern Michigan or anywhere.

Kirsten Mowrey: What was the Native American Languages Act about?

Stacie Sheldon: [With] the Indian Removal Act [of 1830, which forced relocation off of tribal lands], other laws that were passed, and the general atmosphere, it’s fair to say that our language was really being suppressed and erased. For instance, in boarding schools, children were beaten for speaking their language. I don't want to say it was a felony to teach or publish in the language, but it certainly wasn't being done. In 1990, the Native American Languages Act lifted the prohibitions against the language that had previously been established.

I always knew I was Native; I just didn't know anybody that spoke the language, or nobody talked about it. [In] Michigan there’s some people who know some language, but most of the fluent speakers of Ojibwe today are from Northern Minnesota or parts of Ontario. They're not in Michigan. Very few in Wisconsin.

Kirsten Mowrey: Originally, Ojibwa was an oral language. On Ojibwe.net you explain the sounds, with native speakers coming together to talk about subtleties and nuances of the language.

Stacie Sheldon: After that act was passed, there was a convention of Anishinaabe speakers and advocates, academics and linguists to decide on what should be the standard writing system for the language. They selected what's called the double vowel orthography, which does make it really easy to phonetically understand how to make the sounds. But then there are still [nuances] like a double O will sound like an “o” in some communities and a “Ooh” [in others]. There's still variations, but it’s much simpler to read and make the sounds accurately than in English.

Kirsten Mowrey: What happened after you graduated college?

Stacie Sheldon: The tech boom was happening. I got a job building websites at just the right moment in time. I was in a long-term relationship with a man, and he wanted to move to Ann Arbor. I didn't think going home would be a good idea with both of us working in tech, so we stayed downstate.

I had a real experience when I first went to college of "nobody here knows that I'm a Native American."[Stacie is an enrolled tribal member of the Sault Ste. Marie Ojibway.] A city environment is really different than a northern Michigan environment. There's not really anybody talking or thinking about American Indians down here, as opposed to the hunting and fishing squabbles of Northern Michigan. It really was much later when I started doing more with the culture and the language.

Kirsten Mowrey: What moment do you remember as being THE moment when you really started working with the language and the culture?

Stacie Sheldon: I remember writing poetry in college and trying to use what I thought were some Ojibwe words from some literature that probably weren't even accurate. It wasn't until 2006 I found a language table at the University of Michigan and realized that there were people who were working together, forming language nests, and finding ways to bring in fluent speakers. The University of Michigan had an Ojibwe language program around that time and Ann Arbor was a place where Ojibwe language stuff was happening.

Early [2006], my friend Margaret [Noodin, co-founder of Ojibwe.net] and I,we would drive to Zwiibiwing Center in Mount Pleasant to Nokomis Center in Lansing to go to classes. Now there's more options, but at the time, there wasn’t. [Creating] Ojibwe.net [initially] was, “Hey, we found some worksheets and took notes” and shared them with each other, for the foundation.

Kirsten Mowrey: I was looking around the website and the breadth and depth of resources on there are amazing. I'm sure you've built that piece by piece by piece.

Stacie Sheldon: Some of it has had to be refreshed and updated because it's been there so long, but yes, it's 20 years of materials. I feel like the earliest form was really a list of resources. Margaret was in academia, so she was able to get us resources to bring in an audio person who supported us for a while. You could go record with his stuff and he would send us nice files. Nowadays we use iPhones for everything. We did get grant support for different aspects of ojibwe.net to pay for the domain name and the web hosting services. But for the most part, we've paid for everything ourselves.

Kirsten Mowrey: Wow. Out of pocket. How has [the language community] evolved from when you and Margaret started?

Stacie Sheldon: There's a lot more online. If you wanted to take a class out of Bemidji (MN) or Trent University (Canada) you can find online classes. Tribes often have programs where they'll run a Zoom class for a certain amount of time. There's online language tables. There's social media now. There's language-based words of the day and all this other kinds of stuff that didn't exist at the time. I think it's so much easier to access and learn the language now than it ever has been.

I feel like the work that we do [is] for educators. A lot of teachers use our resources. The work that we do help[s] people take their work and help[s] them put language as an aspect of what they're doing. That has felt important to me. Is it an important website? I don't tend to think about it that way.

Kirsten Mowrey: Robin Wall Kimmerer was in town a few weeks ago. I'm going to ask you the question I asked her, which is, given how language shapes thinking, how important do you feel it is for people to learn Anishinaabemowin, including people for whom that’s not their culture?

Stacie Sheldon: I would like people who live in the Great Lakes Basin to have exposure to the language. Wisconsin has something called Act 32, where Native American curriculum is mandatory. Michigan doesn't have that. We're sharing this basin together. The Great Lakes Watershed and [children] should have an awareness of who they're sharing it with. I don't think they do. There are massive treaty boundaries. [For example,] the Treaty of Washington of 1836 is a really important treaty. I don't know very many people who could tell you much about it. [The Treaty of 1836 was initiated, under duress, by northern Michigan tribes to avoid removal to Kansas and Oklahoma. Read more here: nps.gov/articles/leaving-our-native-country-forever.htm].

I don't know that you need to learn the language. I think you could learn a lot about the language and have some exposure to it. It could be an intro series and there would be great benefit to that. The language is so dominant, it doesn't occur to English speakers to think about how their worldview is informed by their language.

I just did a class recently where I talked about the Detroit River, which is part of the Great Lakes watershed. I said, the French call this " Dé troit " and that means "the passage." That's how you use that body of water. And it's how it's come to be used—they’ve dug it out to make it deeper for ships. We called it Waawiyaatanong which is a characteristic of the river where the water goes around because it used to have, may still have, whirlpools. I imagine there's less of them now with the water being deeper. We named it based on a characteristic of itself, because we see water as a being and having character, personality, and power. The Europeans named it for how we would come to use it. I don't think that English speakers ever think about anything like that. And they don't have to because they're never challenged on needing to learn another language.

Kirsten Mowrey: I know you have a singing group. Do you sing traditional songs or new songs?

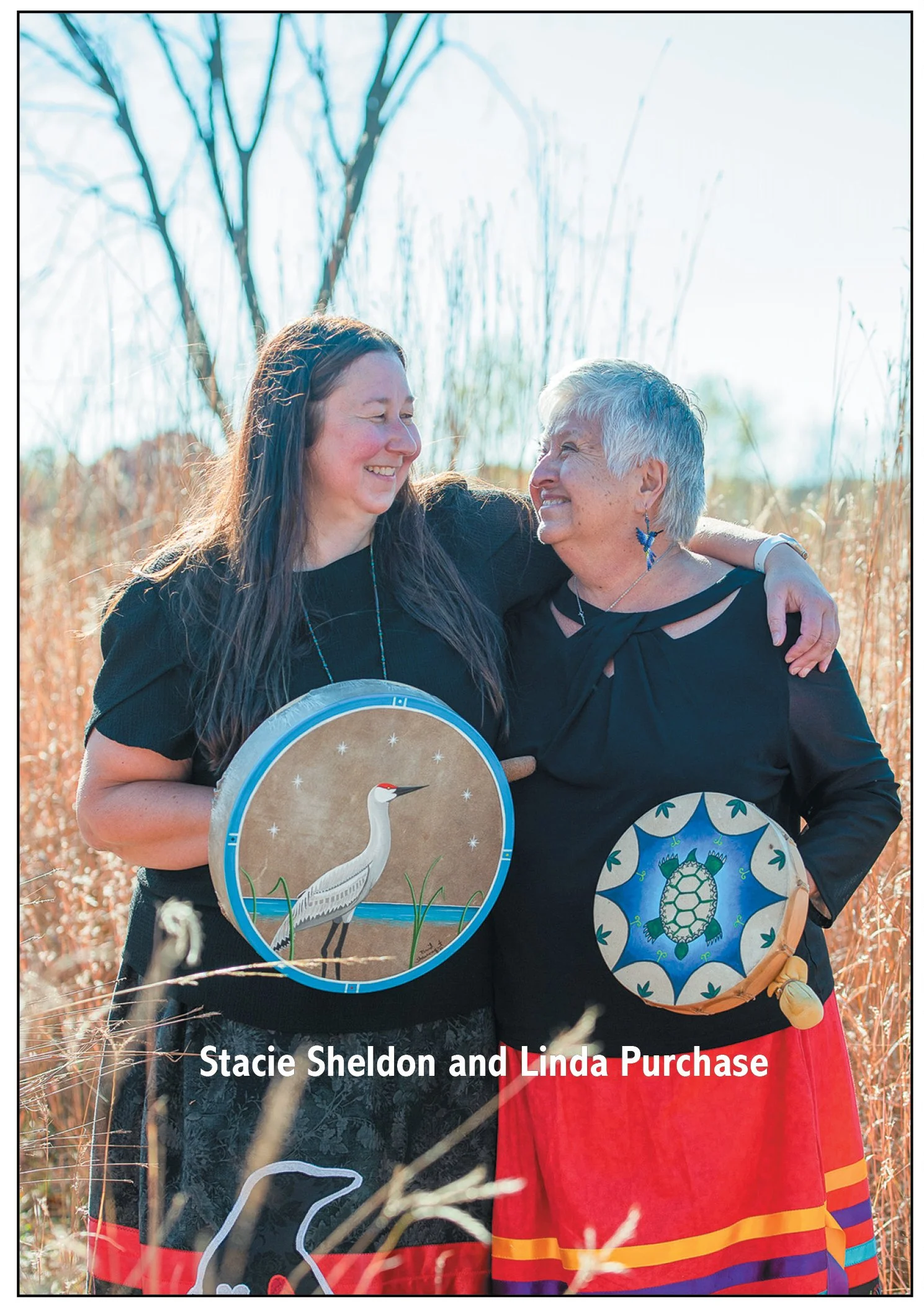

Stacie Sheldon: It's enjoyable to sing in the language. I started a singing group with my friends Linda and Marsha in 2008. Two years ago, I started the group that I have now which is Asiginaak-Negamojig, Blackbird Singers.

We sing songs for ceremony or family, like a lullaby, and learn those songs together. Our goal for our particular group is to sing songs in Ojibwe. There's plenty of songs that have been made that are in English or just vocables. We tend to mix vocables and Ojibwe language together. We do sing newer songs, because language revitalization means that you are creating new things and not just sticking with the older things.

Kirsten Mowrey: I don't know what vocables are.

Stacie Sheldon: For example, if you're [singing] "way ahe.” It's not a word, but people are singing sounds.

I think vocables really [came about] during that time when it was very prohibited to speak in languages. People did sing and because of language loss, people did sing a lot in vocables.

Now with language revitalization, I think we'll hear more and more songs that have some vocables but are more of the language of intent.

Kirsten Mowrey: What has it meant to you to create this website that is part of the re-blooming and restoration of your traditional culture and language?

Stacie Sheldon: Since you're a fan of Robin Wall Kimmerer, you probably understand that she has expressed that if you have a gift, you have a responsibility. I had this whole accidental career in tech, which was not ever what I had imagined that I wanted. But I have learned the skills to create a website, and that has been a gift. I felt the responsibility of that has been the work that I've done on Ojibwe.net.

We have, due to genocide and the boarding school era, real problems in Indian country. [In] any socioeconomic factor or indicator you can think of, we're going to rank the lowest. Poverty, incarceration, education, alcoholism… our suicide rate is insane. Native kids are 20% more likely, I think, than non-native kids to commit suicide. To me a lot of that is language and cultural loss, or this weird in between of not having language and not understanding who you are. I get overwhelmed when we think and talk about that. You have that feeling of what can I do? Ojibwe.net has always been my answer to that [question] of what can I do? All I can do is keep working on this language revitalization project. I don't know how to fix any other problems. I don't have any other gifts to fix problems in any other way.

Kirsten Mowrey: Part of the work that I have been doing for myself is to be with the question of how do I live well in this place? Within the Great Lakes watershed, reckoning with the history of actions taken by settlers in this place. What can I do to start to face these wounds that are here in our culture and in our communities? When I've hosted group events, I do a land acknowledgement. I understand that acknowledging needs to recognize not just traditional stewards of the land, but also the people who are still living here. Do you often encounter when you and your group do public events that people are surprised native peoples are still here?

Stacie Sheldon: Yes. We've gotten questions like, do you live in tipis? We've gotten some alarming questions. A lot of surprise that the language still exists. A lot of, “You don't look like a Native American.” A whole range of things that we get asked are pockets of ignorance. Some people get grouchy about those questions, comments, or perceptions. I have made my peace with that.

I feel like we know where our stories aren't being shared in school. Unless somebody got curious and really pursued that information themselves, and even then, [with] the internet you’re not always finding accurate information. I tend to just look at those as opportunities to address some of these things and to not let it impact the day and experience that I'm having.

Kirsten Mowrey: What would be your hope for people of European descent to learn from ojibwe.net, if as a result of this interview, they decide to take a look at the website?

Stacie Sheldon: I would like them to know that our language is here. The Great Lakes Watershed is the ancestral home of our language and the traditional home of our language. [Editor note: Ancestral references the many generations that have lived here. Traditional references language shaped by Land in a continual relationship, and honors that, unlike other peoples, Ojibway people were not removed to other parts of the country.] There's a lot of things that are unique about Ojibwe that are also unique to the watershed.

At some point I'd love to see people want their kids to learn about the language and the culture—for them to demand that to be in the curriculum. I think to us, what's really important to all Native Americans is, or all these people who are tribal, is our sovereignty. We need to be recognized as a people who are unique and who have a language and it's alive and it's here now. That would be a great takeaway just in and of itself. Michigan has 12 federally recognized tribes and a number of state-recognized tribes. I always feel like that surprises people.

Kirsten Mowrey: What is your focus right now?

Stacie Sheldon: We have been refocusing a little bit on our lessons. We have been exploring the use of reels more. I don't know that anybody's learning the language by watching reels, but it somehow becomes part of the day and part of your life. I feel like the language world is very active. Young people have so much more access to the language right now that we're going to have to keep up with them. You can't, at a young age, start sharing all these songs and really teaching the language and not having anything to support it after that. I feel like we're busy and it's hard. We all have full-time careers outside of ojibwe.net.

Kirsten Mowrey: Anything else you want to say about Ojibwe.net and its future?

Stacie Sheldon: Ojibwe.net is always the outcome of everything else that's happening. I think our language teaches us about our beliefs and about how we see the world. If we know our name, we know our place in the world. And if you know your place in the world, you know your name, and those sorts of relationships are all part of that work that we're doing. I've been doing this work for a really long time, and I suddenly feel much more community engagement and things happening. I don't know, I couldn't say what's behind that, but it seems like an exciting time right now.

The webpage is the outcome of whatever happened: a garden being built, signs going into a school, decolonizing a map [revising Eurocentric maps to show Indigenous names, territories and histories]. Those are things that are happening in the world, and the thing that shows up on ojibwe.net is a piece of that story.

Kirsten Mowrey: I want to say thank you for being willing to talk to me, and I want to acknowledge that the health and wellness community has not always been in right relationship with the Anishinaabe community.

Stacie Sheldon: When I first got your email, I thought, no. Then I thought healing doesn't happen just because we want it to. Reconciliation doesn't happen by skipping all the reconciliation. I don't want to be the person that just slams doors shut and is a jerk. I have enjoyed talking to you, so I appreciate you said that.

Kirsten Mowrey is a bodyworker, grief tender, and a lifelong lover of the Great Lakes watershed. Visit her online at kirstenmowrey.com.

Twenty years ago, Stacie Sheldon and Margaret Noodin founded the website ojibwe.net in Ann Arbor, beginning the hard work of revitalizing Anishinaabemowin language, speakers, and culture. Their work is part of greater regional shift, which in 2025 saw Detroit’s first pow wow in thirty years, a major exhibit open at the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the arrival of Ann Arbor District Library’s mascot, Akako G. Shins (“little groundhog” in Ojibwe).