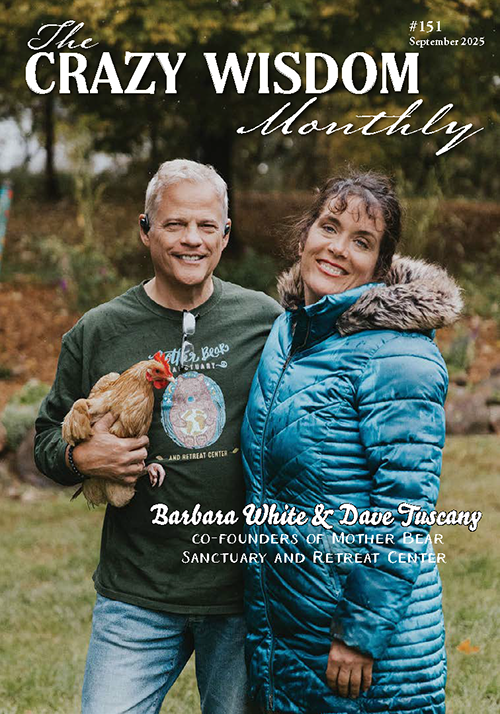

By Catherine Carr • Photos by Hilary Nichols

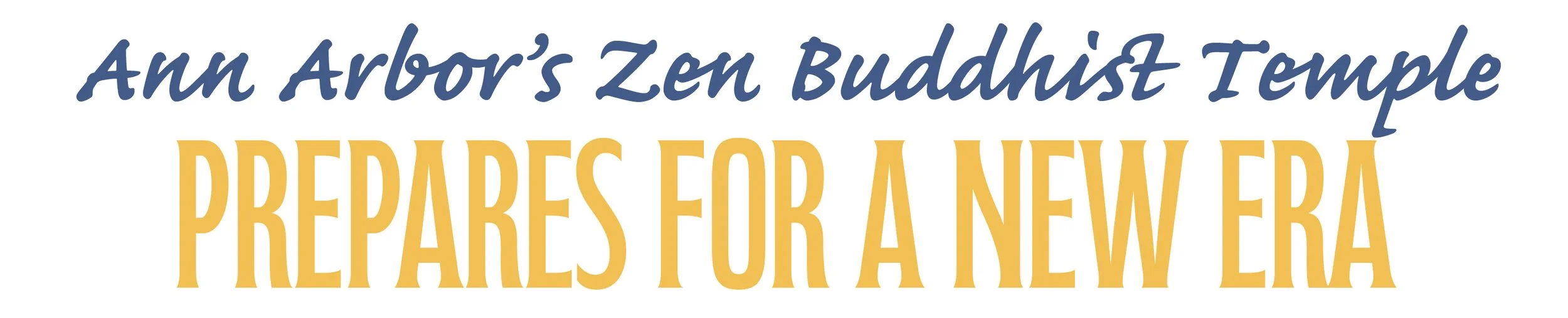

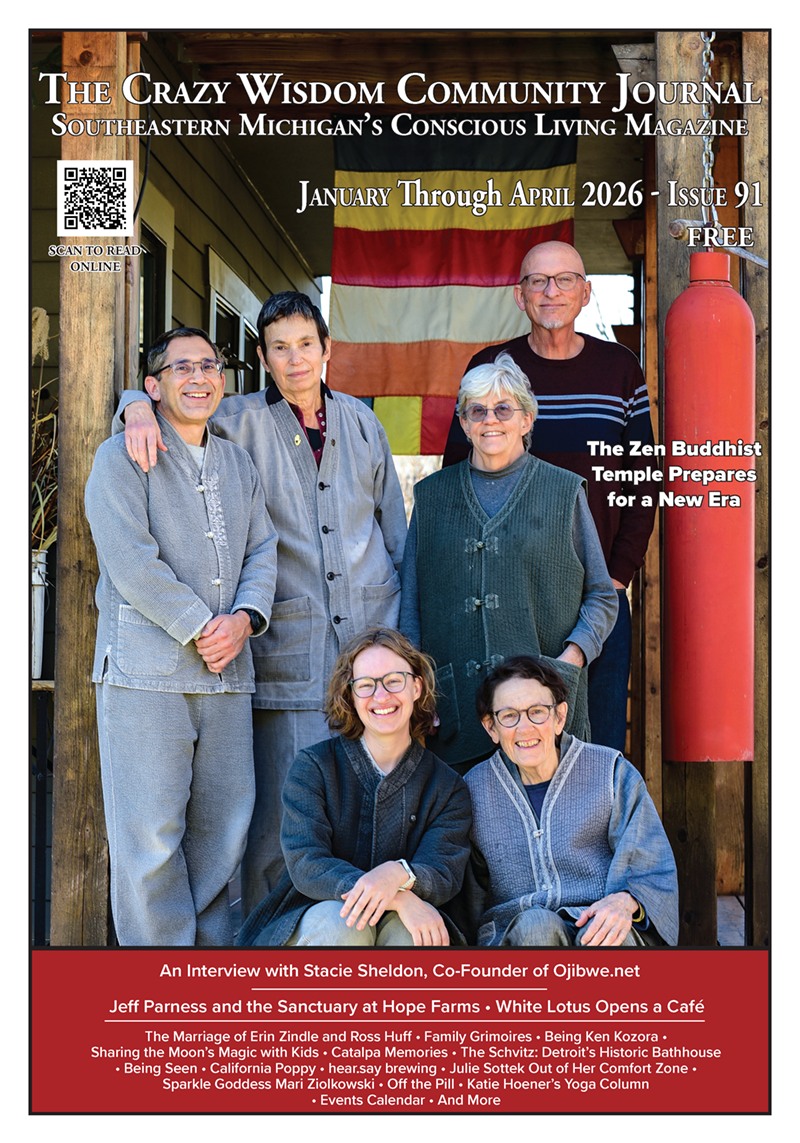

Six years ago, I wrote “Breath and Spirit,” an article for the Journal about my experience living at Ann Arbor’s Zen Buddhist Temple. The clarity and support I found there helped me to launch my writing career (https://www.crazywisdomjournal.com/thecrazywisdomjournalonline/2019/9/1/the-science-of-breath-and-spirit?rq=breath%20and%20spirit). This month, I returned to the Temple to interview Reverend Haju Sunim again, and three of the six new teachers who are preparing to take the reins as she heads toward a partial retirement.

Ann Arbor’s Zen Buddhist Temple offers a rich variety of community and spiritual wellness services to the Ann Arbor community. In addition to its weekly Sunday Services, which offer community meditation and dharma talks on ethics, virtue, and joyous living, the Temple offers meditation classes for beginners, monthly meditation retreats, weekly yoga classes, a Mindful Parenting group, a prison dharma program, and a 12-step inspired addiction recovery group which can be attended both in-person and via Zoom.

The Temple even offers a residency program in which people can live at the Temple for periods of weeks to months and participate in the daily meditation services and communal meals for members. In 2019 it upgraded its residency facilities with the construction of a new Sangha House which is powered by geothermal energy and equipped with a new community kitchen, conference room, and bedrooms for those seeking peace to stay in.

As we enter the late 2020s, the American Zen community is preparing for a changing of the guard. With many of today’s Western Zen teachers trained during the 1960s and 1970s, temples and teaching centers across the country are preparing to hand leadership to a new generation of students and enter a new era of American Zen Buddhism. For the first time, the leaders will be largely Western people who were taught by other Westerners in the late 20th century--not Westerners who were taught directly by Zen teachers from Asia.

Zen Buddhism has been a slowly growing presence in the West since the 19th century. Among Buddhist branches, Zen was particularly appealing to many Westerners due to its emphasis on meditation and reflection as tools for facilitating compassion and direct spiritual experience. Rather than emphasizing obedience to religious authority, Zen offered poetic meditations on beauty and virtue, and practical tools that anyone could use to experience these things.

Zen has been present in Asian American communities for as long as Mahayana Buddhists have been living in the United States. The first white Americans to embrace Zen Buddhism were artists and philosophers who worked with Buddhist teachers to support the translation of Buddhist teachings into English.

Transcendentalists like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson found wisdom in the poetic nature-based parables of the Lotus Sutra. After the 1893 Parliament of World Religions, American attendees formed relationships with Japanese Buddhist teacher Soyen Shaku that resulted in him and his student, D.T. Suzuki, moving to the United States to teach Zen and publish books about Buddhism and Taoism in English.

Zen came to be more widely known outside of Asian American communities in the U.S. during the social change of the 1960s and 1970s, when many Americans left conservative churches in pursuit of spirituality which would support pacifism and the personal experience of connection between all beings. The Buddhist Society for Compassionate Wisdom and our own Rev. Haju Sunim trace their Zen roots to this time.

Rev. Haju’s teacher, Rev. Samu Sunim, came to North America in the 1960s. Samu Sunim entered a Buddhist monastery after being orphaned during the Korean War and completed his Zen training under Master Solbong Sunim. When he was conscripted into active military service despite being a monk, he left for Japan, and then for New York City. There he followed the Asian tradition of traveling Buddhist monks who live off of donations while teaching Buddhism and meditation. He founded what was then called The Zen Lotus Society in New York City in 1967.

In 1971, Rev. Samu Sunim began teaching in Toronto, eventually gathering a group of followers in a former flophouse. He met the woman who would become Rev. Haju Sunim, when she rode up to morning meditation on a motorcycle one day in 1976. At the time she was Linda Lundquist, a Vancouver-born teacher in Canada’s alternative schools. She soon became a dedicated student of Rev. Samu Sunim and began living in the Ann Arbor Zen Buddhist Temple shortly after its founding in 1982. She was officially ordained as a Buddhist priest in 1989.

Now, Rev. Haju Sunim is preparing for a partial retirement. “Partial” because she, and Jeolrector Maum, plan to continue to reside at the Ann Arbor Temple and will play important roles in its operations. But they are preparing to hand over the essential duties of running the Temple to a team of six lay teachers who have been in training for over a decade.

I met with three of these teachers, as well as Rev. Haju, for an interview.

“Figuring out what is essential to continue this work is an important responsibility,” Jagwa, one of the lay teachers who will assist with running the Temple, said. She told me of her own path to becoming one of the Temple’s leaders beginning with her first attendance during her graduate school years at the University of Michigan.

“I was invited to attend Sunday service by a friend,” she shared. “Afterward, I felt more settled and less stressed. When I attended my first meditation retreat, it was like getting on an airplane and not knowing where you’re going to arrive. I’d never meditated for eight hours before, and I didn’t know what it would be like.”

The monthly retreat included “work practice”—a foundation of Zen which treats everyday labor as an important gift to the living world, and a potential gateway to enlightenment. To her dismay, Jagwa was assigned to scrub one of the Temple’s bathrooms—a task she hated at home.

But as she scrubbed the tile floors of the Temple bathroom, she experienced a sense of peace.

“It was surprising and magical to me that my mind could be like this,” she told me. “I was so present in that moment. My mind wasn’t trying to push away things that it didn’t like.”

Jagwa has now been practicing and studying at the Temple for thirteen years.

Mosamsam, another member of the leadership group, told me that this would continue to be the Temple’s mission moving forward. “Our mission is to provide space for mindfulness and meditation specifically from the Buddhist perspective. It’s not just about personal experience: it’s about meditation practices that allow us to investigate our own minds, so that we may be more able to act in skillful, ethical ways in the world.”

I relate to Mosamsam’s statement at a deep level. In today’s world, many have commented on how difficult it is to maintain morality in one’s actions. When so many of the products and services we’re offered in daily life have deeply unethical roots, how does one muster the moral fortitude and executive function to make the more ethical choice?

Fortunately, meditation has been clinically shown to increase executive function. It’s easy to personally experience how actions and decisions become more conscious and intentional after Zen meditation. The enhanced sense of peace and well-being come from this clarity of mind.

Five of the six members who are slated to take over temple leadership responsibilities are lay teachers with full-time jobs in the outside world. “We have full-time jobs in the outside world,” teacher Magamok told me. “I like to think that people who come to the Sunday service can relate to us easily for that reason.”

Magamok first encountered Zen teachings while studying karate during high school. His teacher was a philosophy professor at Penn State who required that students memorize the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path of Buddhism as part of their green belt exam. “The dojo’s motto was ‘Conquer oneself,’” Magamok explained. “I loved that, and I later learned it was a saying of the Buddha.” The full quote from the Dhammapada is:

“Though one should conquer a thousand men in battle, yet he who conquers himself is the noblest victor.”

— Dhammapada, Verse 103

“In Zen,” Magamok said, “we’re not putting our trust in an external power. It’s about observing and learning how your own mind works.” Now, he wants to give the same gift to seekers who come to Ann Arbor’s Zen Buddhist Temple.

“This time is like being in a crucible,” Rev. Haju told me. “These teachers have all been part of this community for close to twenty years, but my body of experience is not theirs. So, we have to ask: where’s the wisdom here? Where’s the compassion? What is essential for this work to continue? How do we cultivate mindfulness and compassion here and now?”

The importance of these questions, and the mindful consideration being given to them, is palpable in the body language of every Temple member I speak to. Deep contemplation of one’s actions is a gift of Zen practice, and for them, this is not just about continuing a meditation class or an ideology. The Temple is a 44-year-old residential community which has always been led by Rev. Haju. It is a community and an institution which is undergoing a seismic shift.

Yet, I don’t fear for its future. As I speak to three of the six dedicated teachers who have stepped up to take over leadership, I see stability. I see people who share the same core understanding of the Temple’s mission giving thoughtful consideration to what needs to be done.

Rev. Haju emphasized to me that the temple is in a state of fluid evolution, as all parties involved contemplate the best ways to handle responsibility and authority in the era to come. “To say there is a new leadership team with job titles is not quite right,” she told me.

“This is all good hard work,” Rev. Haju says, “and I look forward to its flowering.”

Those interested in joining the Zen Buddhist Temple for a Sunday service, class, or retreat can find their events and contact information at ZenBuddhistTemple.org/AnnArbor. Sunday services are open to the public at 10:00 a.m. on Sunday mornings. The Zen Buddhist Temple is located at 1214 Packard Street, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Haju Sunim (Linda Lundquist) has been a student of Samu Sunim since she first showed up on a motorcycle for morning meditation in Toronto in 1976. Haju Sunim is the resident priest for the Ann Arbor Zen Buddhist Temple in Michigan, where she has lived since 1982. Much loved, Haju is an example of "an ordinary Buddha, a Buddha of deep humility and compassion" according to Samu Sunim.

She was ordained as a priest by Ven. Samu Sunim in 1989 and received Dharma transmission on July 3, 1999. On this occasion, Samu Sunim gave this verse to Haju Sunim:

Dharma is the Universe.

Earthworms and flies are Sangha;

Rocks and soil, Buddha.

Play with your boundless heart

Enjoy unlimited action.

Haju Sunim was born in Vancouver, Canada in 1944. She taught in alternative schools in British Columbia and in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser College. As a single mother, Haju raised two daughters.

Jagwa (Kelly Davenport) is a lay dharma teacher at the Ann Arbor Zen Buddhist Temple. She completed teacher training four years ago and has been a sangha member for 13 years. Inspired by the Zen saying, "Even the hedgerows teach the dharma," Jagwa finds glimmers of Buddhist teachings woven into everyday life—from baking bread, to working in software development, to weightlifting. As a teacher, she uses the material of her life to make the case that we can always come home to our fundamental stability, discovering the joy and juiciness of interconnection. She lives in Ann Arbor with her husband, Ian, and a lot of books.

Chijang (Cliff Brown) began practicing Buddhism in the mid-90’s and soon after received the five lay precepts. In 2003 he ordained as a Buddhist Monk in the Plum Village Tradition under Ven. Master Thich Nhat Hanh and received the Dharma Name Chan Phap Vu (True Dharma Rain). In 2011, he was ordained as a Dharma Teacher. After about 19 years as a monastic, he decided to return to lay life but yet still dedicated to the practice and understanding the teachings of Buddhism. Currently, he resides at the Ann Arbor Zen Buddhist Temple where he reconfirmed his lay precepts and received his Dharma Name Chijang.

Maum (Gloria Cox) grew up in the rolling hills of western Iowa. When her work led her to Michigan, she came to the Zen Buddhist Temple, where her commitment to the Dharma deepened over several years. She was ordained as a lay Dharma Teacher in 2010 and then as a resident Zen Priest in 2016. With a heart of loving kindness and peaceful dedication, Maum teaches meditation classes, leads retreats, and oversees the temple schedule.

Magamok (Mike Umbriac), whose Dharma name means "Mountain Ash Tree" in Korean, grew up in the mountains of Northeastern Pennsylvania. He took a course about Buddhism in college in the 1990’s, then tried to study Zen on his own using books and began attending the Zen Buddhist Temple in 2003. After several years of volunteering in different capacities, he began studying in the Temple's formal training programs in the fall of 2019. At the University he is a lecturer in engineering, where he does his best to help his students approach engineering projects with a calm and systematic mindset. He volunteers at the temple on some weekends.

Catherine Carr is an author and cultural documentarian from Ann Arbor, Michigan. She now lives in Chicago with three cats, two snakes, a giant Fenris wolf, and various wayward witches.She has spoken on Pagan spirituality at the Parliament of World Religions, the University of Chicago, and other venues. Her books, World Soul: Healing Ourselves and the Earth Through Pagan Theology and Breaking Your Bonds: Finding Freedom Through Adversity are available wherever books are sold, including Amazon, Bookshop.org, and BarnesandNoble.com.

Buddhists comprise only around 1% of the U.S. population, yet Buddhism has exercised a disproportionate influence on American culture, especially since the end of World War II. Buddhist images, whether of Shakyamuni or Tibetan mandalas, seem ubiquitous. Buddhist-based mindfulness practices are taught in countless American institutions, from prisons, to schools, to hospitals. And influential cultural figures, including actor Richard Gere, composer Philip Glass, and poet Jane Hirshfield, speak openly of their Buddhist practice.