By Audrey Hall

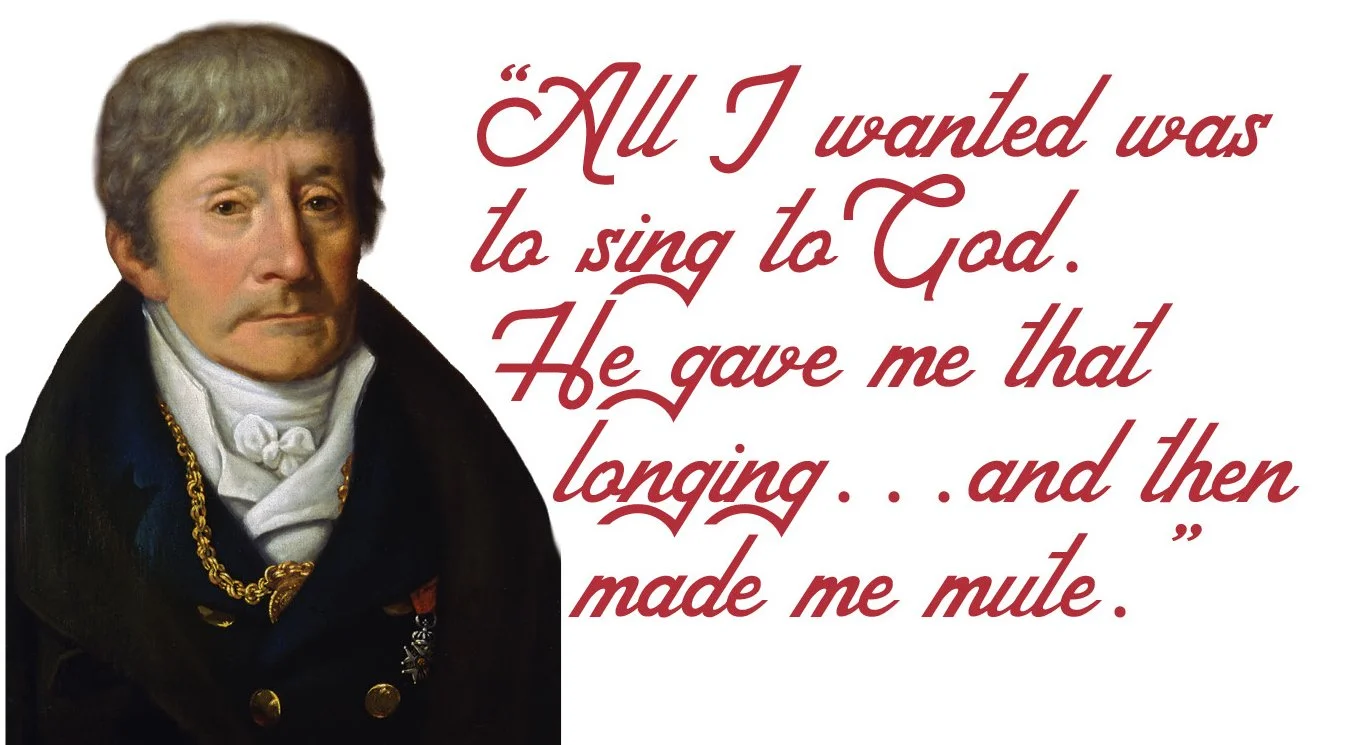

These words are spoken by Antonio Salieri in the 1984 film Amadeus, a historical fiction about his relationship with Amadeus Mozart. Though amicable colleagues in reality, this entirely fictional representation of these two individuals and their story portrays a demented Salieri who believes he is tormented by God through Mozart. On the surface, the film explores the fine line between serpentine jealousy and tender admiration between colleagues. In the spiritual realm, we see a deal with God gone wrong. Salieri swears celibacy in exchange for talent, but in the end believes himself mocked and tortured by the very same God to which he swore his oath. He believes God instead has chosen Mozart, a vulgar sinner, to be his divine voice in music.

Whether or not one believes in the Christian God, it's clear that the spirituality of Salieri is corrupt and destitute. He calls the death of his father a “miracle” as it affirms the legitimacy of the pact he’s made for the furtherance of his desire to compose music. While a Christian might say this is not the work of God but of man or the Devil himself, an occultist may look to the human psyche as well as ancient spiritual concepts to explain Salieri’s experience. One may also point out that this is a fictional story and thereby requires no such explanation, but I believe these pacts and affirmations, or betrayals of them, occur throughout human history and society. Amadeus, even if an entirely fictitious depiction of these two men and their entanglement, is realistic in its depiction of this spiritual phenomenon.

In analysis of what occurs between God and Salieri, let’s explore the ancient occult concept of the egregore. Used to describe the Watchers in the Book of Enoch, this word has taken on a broad spectrum of meaning circling the relative consensus of “a thoughtform or entity existing outside of physical reality created from and sustained by the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of a collective.” In plain speak, an egregore is something between an imaginary friend, an idea, and/or a field of energy shared by a group of people. Some occultists have speculated that the very Catholic God Salieri turns to in Amadeus is an egregore, conjured from and empowered by the shared belief of Catholics the world over.

Salieri’s God is distinct from the Catholic God. Obviously, his ability to interface with the Lord directly as a layperson reveals this distinction, but the Catholic God is also characterized by mercy and holding all life sacred. This is hardly the nature of an entity capable of murdering a boy’s father to secure his ambitions. A Christian might call this the Devil posing as God, a favorite game of Old Scratch. Given the folkloric tendency of demons to facilitate contracts on false pretense, this conclusion is sound. Taking this again from the occultist lens, I believe Salieri has made a dangerous departure from connecting with the egregore of his people. His pact is with a wicked doppelganger of God, a tulpa of his own making.

While the distinction between tulpas and egregores is hazy and at times indiscernible, most commonly egregores are understood as larger abstracts born of collective consciousness while the tulpa requires only one person’s focus and concentration to manifest. The origin of the tulpa is in Tibetan Buddhism wherein buddhas, who have transcended time and space, manifest physical emanations to lead others toward enlightenment. Western occultists took this concept and, whether by arrogance or ignorance, reversed the order. Theosophists believe we can personally or collectively emanate a conscious being or “thoughtform” through heavy concentration and practice. With enough vitality and intention, these tulpas can even become autonomous or dangerous. It is my belief that practice is not necessary to the creation of tulpas, and that the process can be entirely unconscious and accidental.

In the case of Salieri, through his own pride, vanity, and selfish ends, he has severed himself from the Christian egregore and made a pact with a being constructed from the raw concentration of his frustrated, repressed ambition. His aforementioned father cared nothing for his son’s desire to make music and therefore became an obstacle in the eyes of Salieri. Hence, his death was a miracle Salieri retroactively attributed to the pact made with his tulpa, thereby feeding its power. Eventually, he attributed his fame, success, and talent to his deal with God, so much so that the tulpa became autonomous and dangerous. He is then confronted with Mozart, a vulgar youth more talented than he could ever hope to be, which leads to Saliere to believe the tulpa he calls God has betrayed him. He goes as far as to cast a cross he keeps at home into his fireplace, declaring war on God by destroying Mozart.

What strikes me about this story is not only the way it plays out these occult concepts but also the way it holds reflections to my own life. Salieri, disturbed and wicked as he may be, was only a child when he spoke with God and formed this tulpa. Many children, including myself, have made this attempt to broker their wants and needs with an underdeveloped understanding of their respective egregore. Obviously results vary ruthlessly, leaving children to affirm or deny their connection to the egregore versus a tulpa of their own making.

In my own life, I knew as a child I did not belong in the church I was brought up in. I was from a very young age terrified of God and terrified of damnation. The backwoods Methodist God I learned of each Sunday was like a blissful cloud with eldritch horrors hidden beneath. While preachers waxed poetic about the ethereal beauty of heaven and the loving nature of God, there was also talk of the desperate plight of lost souls. I always knew I was a lost soul. Even after giving my life to God, I still felt his All-Seeing Eye staring deeply into me and judging me unfit for the kingdom of heaven. In this case, I would argue that the egregore created within the rural community I grew up in was accurately represented in the terrified eyes of a young, confused child who would later discover she was transgender.

Cast out by the egregore of backwoods Appalachia, I became quickly surrounded by tulpas both manufactured by my own psyche and implanted by my surroundings. I found solace in some, but their power was nothing compared to those sourced from beyond. On one side were the terrifying angels of God dragging me toward the light of conformity, and on the other were demons taking me further into darkness. These tulpas were autonomous, dangerous, and ready to make deals with a scared child with no understanding of what that meant beyond an already predetermined and unavoidable damnation.

When you grow up in a community so engendered by groupthink, a spiritually lost child has no guidance and cannot share in the light of their chosen egregore. Your alienation becomes the breeding ground of dark pacts, much like the deals made between Salieri and his doppleganger of God. These tulpas went on to torment me well into adulthood. For almost twenty years of my life, I experienced visions of Hell and relentless haunting. If it weren’t for ritual work I’ve done in the last year of becoming a witch, I would still be as tormented as Salieri at the beginning of Amadeus.

The difference between Salieri and my experience with tulpas and egregores lies in his inability to cut ties with, integrate, or destroy this malevolent spiritual presence he unwittingly created. Knowing would be half the battle, but even if he knew this God he hated was not his creator, would he truly be able to overcome? Salieri’s defeat at the hands of his tulpa lies largely in the sheer amount of belief and focus he feeds it, first through his fealty and then through his hatred. Once the human mind is thoroughly convinced of a spiritual truth, it seems confirmation bias takes hold and every occurrence in material reality becomes an affirmation. His father’s death, his success, and being taunted by Mozart all affirm the fundamental reality of this laughing thing he calls God.

In my experience, I was forced spiritually underground. I buried myself deep into nihilism and atheism, trying desperately to close my third eye to relentless haunts and visions. This was a matter of survival for most of my adult life. Upon escaping the Bible Belt and moving to Ypsilanti, I found myself finally able to breathe in the mystic again. Here I found power to destroy and/or integrate tulpas as needed and face the egregore of my hometown once and for all. This took a great deal of spiritual exploration, dialogue with other practitioners, and ritual work. I faced the hateful God of my childhood in a grand ritual called the Banishment of Angels, and I have not been haunted by him since.

In material reality, these were psychological exercises I performed to no longer supply belief to the tulpas and egregores causing me harm. My fear and hatred were as potent as love and obedience in the feeding of these abstracts. It sounds simple enough on paper to just stop believing in a concept, but when the development of your mind is so aggressively shaped by that concept, it’s not so easily shaken. This isn’t just true of God. Other immaterial abstracts like gender and race become unshakable aspects of our thinking regardless of scientific evidence showing how bankrupt they are fundamentally. It takes not just a year but a lifetime of work to shake biases and eliminate thoughtforms that cause harm in our lives and the lives of others. It begins with a conscious journey towards the awareness of their presence.

It is my belief that the thoughtforms we create are inevitably reflections of ourselves. It is also my belief that these thoughtforms reflect society, in that we are each unique and subjective reflections of society. One person's thoughtform blends into another, a tulpa becomes an egregore, and then a piece of the egregore becomes another tulpa. The cycle continues for thousands of years, fed by generation after generation of human belief systems. Each lineage passed down influences how we think collectively and individually—as early in our development as our understanding of language itself. It is not just God and the Devil playing games of good and evil within the human heart so much as the human heart conjuring spiritual forms to better understand itself.

I believe this is why Amadeus begins with Salieri’s desperate cry of confession in solitude, “Mozart! Mozart, forgive your assassin! I confess, I killed you.” It is in this moment alone that he faces his God and sees himself in the mirror. For the rest of the film, we see him constantly pulled between loving and hating himself, deserving everything but achieving nothing. He cannot abandon his tulpa because it reflects the cold mockery of his own heart, never being enough in his own eyes once Mozart’s raw and miraculous talent cannot be ignored. His superiority complex is forever disrupted, even once he’s tortured Mozart to death. We find him bitter and pathetic in the end of his life, delighting only in his torment of a baffled priest trying to save his soul.

Salieri created God in his own image, and saw it was bad. As folks say in Appalachia, “Bless his little heart.”

In Nature’s Symphony, Martin Docherty presents a refreshing and deeply thoughtful perspective on our relationship with the natural world—one that blends science, philosophy, and spirituality in a way that feels both intellectually satisfying and emotionally grounding. This book is neither your typical science read nor a standard spiritual guide. It’s something more layered: a meditation on the sacredness of the universe, grounded not in supernatural beliefs, but in the elegant truths of science itself.