By Sandor Slomovits

The mid-January day I visited Gateway Farm in Plymouth was breezy, and the temperature was in the low thirties with faint flurries falling. At the farm’s small, dirt parking lot off Joy Road, I met Bridget O’Brien who, along with her husband Dr. Charlie Brennan, is the farm’s co-director. After we greeted each other, I said, “Not the best time of the year for me to see the farm, I guess.”

“It’ll be okay,” she replied cheerfully. “We’ll be able to see everything because there’s no snow on the ground. Plus,” she added, “The sorrel is still green.”

Gateway Farm in Plymouth is owned by Mary Emmett and her family. Emmett founded the nearby Plymouth Orchard and Cider Mill in 1977 and established Gateway Farm in 2017. Zoe Arvantis, the Farm’s Markets and Marketing Manager, emailed me that, “Mary’s intention was to create a farm hub offering organic nutrient-dense food to the Plymouth Community.” She then added that, “The farm has diversified a great deal in the last five years. We have gone from offering solely organically grown annual vegetables, to showcasing a variety of food systems. Also, like many farms, when the pandemic hit, we were forced to pivot quickly. We leaned heavily into our onsite farm stand as a distribution hub for pre-order online sales. We partnered with local producers to expand our organic vegetable offering with pantry items, maple syrup, and honey. We’ve continued [doing that] today, expanding our offering even more to include perennial foods, Gateway Farm dried herbal teas and value-added products, CSA memberships, farm swag, and transplants. We’ve re-imagined our farm-scape using a permaculture-inspired vision that weaves together market gardening, food forests, land regeneration and re-wilding.”

I’d heard of permaculture, (short for permanent agriculture, which relies on a variety of perennial crops) but had never seen a permaculture-based farm in person, so I asked for a tour.

We began walking and O’Brien pointed to a number of yard-high berms, crowded with a great variety of plants and bushes, curving gracefully around two small ponds and weaving throughout the thirteen-acre property. “One of the most interesting things about this farm,” she said, “Is that in our perennial plantings we have over 250 different varieties of plants.” She pointed to the berms. “This feature is our food forest--our perennial food system. Eighty to ninety percent of everything that’s planted here is edible in some way, shape, or form.”

I had heard the term “food forest” before and had imagined woods with fruit and nut trees. Here the tallest plants growing on the berm near us were only about three or four feet tall.

“Yes,” O’Brien replied, “This planting is only going on its third to fourth year, depending on the plant. There’s a lot of trees in the system, and most of these were planted when they were this big,” she said, holding her hand about a foot off the ground. “So, we’re already getting some good growth on them. Eventually this will have trees, lots of trees in it, so it’ll feel more like a forest. There are layers in a traditional forest. You have tree layers, shrub layers, ground cover layers, and often vines, too. These [plantings] are meant to mimic systems in nature that a lot of indigenous cultures around the world cared for and worked on for centuries.

We do have mulberries and other stuff that we planted on the other berms that you’ll see are taller than us now. They were planted at the same time but are just happier and grew faster. A lot of food forests are planted kind of like a wild forest, where it’s a bit more of a scatter pattern; there’s a tree here and maybe one over here, but it’s a different species. However, this [food forest] was designed for production. So, there’s a row of serviceberries, rows of elderberries, and we have three patches of honeyberries, but they’re all in one section. As they grow and we harvest them, they’re easier to find. Elderberries are growing really well here. We’ve planted over fifty elderberries on the property; we started harvesting this year—seventeen pounds—second year of growth.”

We came to a small flat area devoted to mints. “We put it [the mints] far away from everything, so it won’t take over. It can grow into the grass, we don’t care. We have a number of varieties that we harvest: chamomile, lavender, calendula, and others. Many of our native herbaceous perennials make really great medicinal teas. A lot of the understory of the food forest are medicinals that we’re value-adding into our herbal tea blends.

We walked by a small pond, and I asked if that had been there before they began farming here. “No, this was all flat or flat-ish. There are wetlands surrounding this property. This land probably also was a wetland, but it was clear cut, flattened, and farmed. Then it was turned into a golf driving range for forty years. When we came to the property, this was just all grass. These ponds were built for the design. These berms were not here, we built them all out of soil from the property. We don’t irrigate with the water from the pond. We have three wells on the property, and we have pretty good water. But we are going to start using this [water from the pond] to irrigate our propagation house.” (A hoop house near the pond.) And we’re setting up systems so that in the future—there’s predictions for El Nino years coming up—we’ll be able to irrigate out of the pond as needed.

The pond is fed by ground water, but there’s also a drain tile from one of the wetlands that comes underground and feeds the pond. There’s an outlet of the drain tile that comes out. When we have mega rains, it can’t process all the water. So, we have an overflow system. We are on a wetland, so water management is number one in the design. Before we did this system, these fields would flood regularly, which made them pretty much unmanageable.”

We come to another berm and O’Brien leans down to pick some green leaves. “This is sorrel, a perennial green, it’s popular in European cooking, and it’s often made into a soup. It’s a really nice green. I think it tastes like lemon spinach.” She hands me a leaf, I chew and agree appreciatively, “Yes, lemony.”

“It’s a nice citrusy flavor,” she says, then adds, “It’s got a fair amount of oxalic acid in it, so you want to cook it more than just eat it raw, but you can definitely dice it up and put it in your salads. It’s really great for soups, stir fries, and flavoring.”

I point to a plant I recognize. “Strawberries?”

“Yes. This is our acid loving berm. Since we built all these berms, we wanted to highlight, or create different micro-climates in different systems. We do not have sand on this property, it’s clay, very heavy clay. People that have worked on this property have said, ‘We’ve never worked on clay this horrible.’ Yet we have all this growing. We brought in three yards of sand, mixed it with the clay and compost and put the berm together. Then we planted blueberries and a variety of serviceberry that like acidic soil. The blueberries are small, but getting there, they’re a pretty hard thing to grow in clay. This isn’t the best place for them, so it’s a bit of an experiment. But, instead of just growing native fruits here, like serviceberries and paw paws—we do have all of those—we also wanted to make sure we had familiar things. So, when people are walking through, they’re like, ‘oh, that’s a strawberry, that’s a blueberry.’ Each berm has a theme. We have some asparagus on this berm and also hazelnuts on the backside of it, and this is lovage on the end. And on all the berms we have different nitrogen fixers. We have either baptisia or speckled alders or redbud trees or one of three varieties of clovers.”

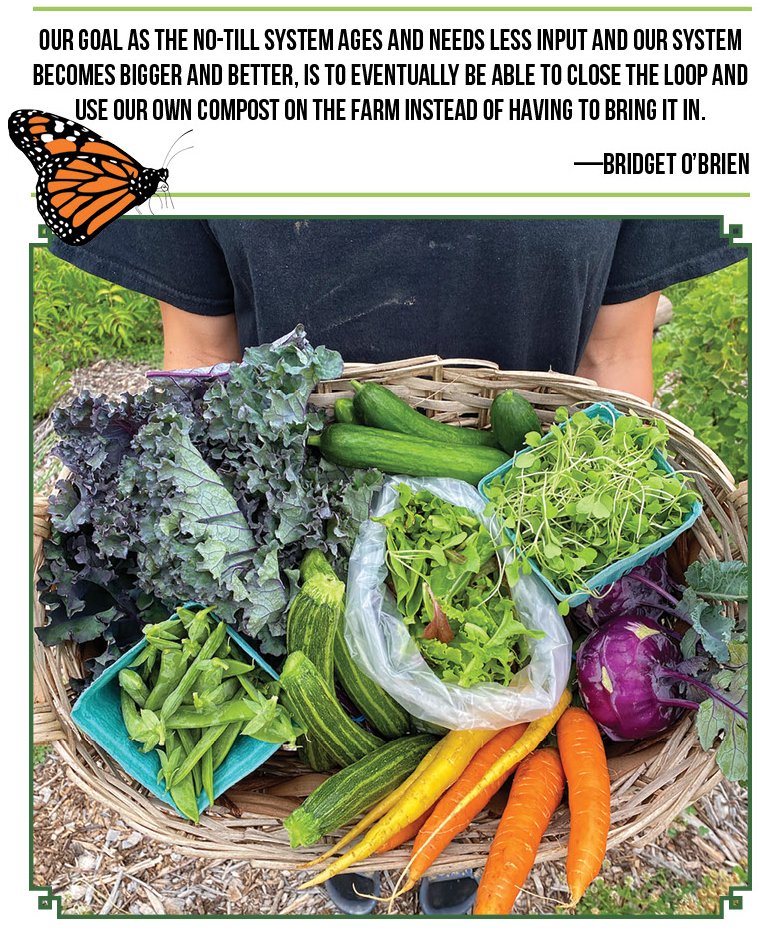

We walked by several tall piles of wood chips and what looked like compost. “We have a tree trimmer that comes and dumps wood chips for us all the time. It’s a service to them and to us. We use a lot of wood chips on the farm, hundreds of yards a year. This is a compost system that one of our crew members, Jesse Raudenbush has set up. He owns Starr Valley Farms, does a lot of work with Project Grow, and also designs really cool vermicomposting systems (worm composting) and we have one of those. Everything over there,” she said, pointing to the piles, “Is material from the property, other than the wood chips. We have piles for our vegetable byproducts and our weed byproducts. He mixes those with the wood chips and turns them and we’ve started producing our own compost on site for our no-till system. Our goal as the no-till system ages and needs less input and our system becomes bigger and better, is to eventually be able to close the loop and use our own compost on the farm instead of having to bring it in.”

O’Brien points to another section of the farm, “There is a little frog pond that drains into the larger pond. That’s our paw paw patch. We have a collection of hazelnuts. There are berms that have some chestnuts on them. In the back corner we have a set of berms that are all planted with things that you can coppice, cut on rotation.” (Coppice is crop raised from shoots produced from the cut stumps of the previous crop. Coppicing is regenerating crops that way.) “There are chestnuts, hazelnuts, osage orange, comfrey, and redbuds back there. They’re all meant for biochar and fertilization.”

The word ‘biochar” was new to me, and O’Brien explained that it’s the residue of ashes of organic material, “Tiny, kind of honeycomb structured pieces of organic matter that hold a lot of nutrients. They can help retain water, [but] they also help the micro system under the ground. It’s something that we’ve added in bits and pieces across the farm, and eventually we’ll be able to start producing our own. We should be able to, starting this year. Our beehives are also back there.”

I marveled at the great variety of farming materials, systems, and approaches. “It seems you have created a whole ecosystem here,” I said. “Incorporating a great many different techniques and plants and animals, as opposed to so much of what modern agriculture seems to be—growing huge fields of a single plant. The fact that you’ve got this whole variety here seems to be part of the plan. It is the plan, right?”

“Yes,” agreed O’Brien. “It’s all about diversity. We’re inspired by permaculture and its ethics and principles, and we designed from them, along with principles of conservation, rewilding, ecopsychology, and a number of other things. Using and valuing diversity is super important. A lot of the flaws that we see with monocultured systems, a lot of the diseases and pest pressures, are not eliminated through these systems but they’re prevented. It also shows a lot more resilience. Some of the experimentation we have going on here is figuring out what works. There’s a chance that we’ll say, ‘Oh, this plant isn’t working. We’re going to rip it out and replace it with a plant that’s more prolific because we are still trying to produce.’ So, if currants don’t seem to be happy here, maybe currants aren’t going to be a part of the long-term system, but gooseberries are a powerhouse here. So, elderberries and gooseberries, we know for sure we’re going to grow more of those. Rhubarb is hard to grow in heavy clay, but we’ve created systems which grow amazing rhubarb. That’s something that’s really familiar, and people like. People like our wild arugula. They like our sorrel. So, we’ll start bulking out on the things that people like but continue to educate them on other things.”

We moved on to a small field with visible straight rows. “These are our garlic beds that are all planted out. Every time we flip a bed, we add more compost and wood chips at varying depths, depending on the quality of the soil and on the crop that’s going in next. We’ve been producing food for about five years and the no-till system is only about two years old.”

Pointing to a large funnel-shaped concrete slab, O’Brien said, “This is our new compost and materials bay. We’re super into soil preservation and covering, and conservation plantings, water management and erosion mitigation. Compost can be an environmental issue when it’s running off into water, and you can’t put it anywhere on this property without it running off. So, it’s going to run into a cattail pond, which will help remediate it.”

As we continued walking, O’Brien pointed to a small stream. “This is our vernal creek that runs as needed. It helps move the water. Water management is a big thing here. Everything in here is a native plant and everything in the gardens are all native plantings too. We do harvest off them. We have rose hips, some serviceberries and mulberries and things over here, but mainly this is for the wildlife and for the sanctuary aspect of the farm.

These used to be thistle fields and we’ve been working on a system of tilling, cover cropping, and cutting at particular times to remove the thistle so that we can plant meadow style wildflowers.” O’Brien laughs as a memory surfaces: “In our last organic inspection the guy comes, and he does his thing, we’re walking around the farm, and we show him this area and he goes, ‘Okay, don’t need to have a talk with you about biodiversity.’”

I spot a small grouping of young trees and ask about them. “It’s a mini forest. We have a funny patch of land in the corner of the property that is hard to farm. It’s a wet spot, the water just pools there. Here we’re trying to demonstrate what a miniature forest looks like and also a different way of setting up a system. Here the overstory, the larger trees, were put in the ground first and we’re maintaining clover and grass underneath them. Then as they get bigger and can drink up the water there and hold space and start to shade things out, we’ll start putting other layers of plants underneath them. Most of this project [the Gateway berms] was planted in one fell swoop. Then we’ve gone in and fixed things or adjusted, added more, took stuff away. Whereas this one, [the mini forest, we started with] just the overstory. When that gets established, we’ll come in and do another phase. It’s demonstrating another way to do it. It also shows that you don’t need fifty acres to plant a forest. You could plant a forest in your backyard if you wanted to.”

O’Brien started working at Gateway at the end of 2018. At first, she and her husband Dr. Brennan were working for Mary Emmett’s orchard and the farm, consulting and designing the various systems, but recently they’ve also come on board as farm co-directors. They have a separate joint business, Garden Juju Collective, and they travel widely teaching permaculture and many other related techniques of sustainable agriculture. (See article on Garden Juju Collective on page 58).

“We live in Ann Arbor. I grew up on Geddes Road, so this is kind of home for me. We’ll be moving into the house on this property so we can better do our jobs and be present. Charlie is actually from England, in Devin. He grew up in England, Singapore, and Australia, so that’s why we travel and teach in all those places.

When I got out of college, I got super into growing plants and gardening while working at Enchanted Florist in Ypsilanti. I fell in love with plants and flowers and started gardening, cultivating, exploring, and finding out more about my roots of family farming. My grandpa used to work all week, but he had this huge veggie farm and used to give all the produce away to his neighborhood.

I worked at Downtown Home and Garden and at a number of nurseries, and I was always learning about plants and design. At one point when I was working in Tecumseh people kept coming in and asking, ‘I want a garden, but I don’t want any maintenance.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, get your glass of wine and your pruners and just go out and deadhead your roses in the evening.’ I started researching maintenance gardening and I came upon permaculture. In the mid two-thousands I took a course in permaculture, fell in love with it, said ‘I want to teach this, I want to share this.’ I took it back to my boss and said, ‘Let’s do more of this.” He said, ‘There’s no market for that.’ I said, ‘Okay, I need to move on.’ I went to other nurseries and tried to learn other aspects of the landscaping world. I realized it was the least green industry of all the green industries. You’d show up at work and they’d come in from the field in their hazmat suits and say, ‘Oh, we just sprayed.’ And I’m like, ‘Okay???’ Then a client would walk in the door ten minutes later and say, ‘Oh, can we go look at these trees?’

So, I went back to my marketing and merchandising background, what I studied in college. Worked with the Co-op in Ann Arbor for a while and started doing more design work and teaching through there. When I met my husband, he had been doing this for a long time. He has a doctorate in social ecology. He trained with Bill Mollison back in the nineties.” (Australian scientist, Bill Mollison is generally credited with helping to found and disseminate the theory and practices of permaculture beginning in the mid 1970s.) “We started designing and teaching and doing all this stuff together and kind of building on all these different career paths that I had at different times. They all came together and made this happen.”

Our final stop of the tour was the large hoop house that will become the farm’s new event space in the spring of 2023. (More about that later.) In a Zoom conversation with O’Brien and her husband, Dr. Brennan a few days later, we reviewed some of the things O’Brien had pointed out on the tour and talked further about other unique aspects of Gateway Farm. (Dr. Brennan joined us from Australia, the Byron Bay/ Mullumbimby area in New South Wales.)

“Permaculture is just one of the techniques we are using at Gateway,” Dr. Brennan began. “We also are using conservation and rewilding. We’re using aesthetics to bring people in, which is more ornamental gardening, if you like. And [the farm] is transitioning toward being an event hub. It’s very much a public facing place, designed to be a hub for community. It’s being designed with quite an investment from the owner to make that possible.

Bridget and I have been involved in food growing for a long time. It’s very romantic, it’s very energetic, it’s usually exhausting, and you’re usually poor at the end of it. So, we’re trying to look for a cleverer farm model than that. Rather than sending tomatoes out and trying to make a living off that, we bring people into the farm experience. People want that horticultural therapy. They want that sense of connection to the land, to healthy food; they want a sense of place, they want to gain skills.”

This brought us to the new event space—half of one of the hoop houses—that Gateway will open soon. “We’re going to make a very welcoming space in there, a teaching center, a meeting space, a space you can hire for an event,” said Dr. Brennan. “When you design outdoor spaces as landscape architecture, you’re often thinking in terms of rooms. What’s this space for? How are people invited here? How are people moving from room to room? So, we’re actually putting a room in the middle of a hoop house. It’s an interesting kind of post-industrial look when you have a nice space inside an industrial building. We’re creating this space so that Gateway can really be a hub for community and education. We want to bring in some high-level teachers, because not many people get to teach out of a landscape as well developed as this.”

“We teach around the world in different locations,” O’Brien said, “And oftentimes we’re scrambling around trying to make one raised bed work to teach a whole lesson on gardening, or one fruit tree or six fruit trees in the middle of a field. We’ve taught two workshops here and it’s been absolutely incredible because you have every single plant that you want to talk about, ‘Oh, let me show you. It’s right over here.’ Being able to show micro-climates and some of the techniques has been really fun.

The hoop house is a season extender, so it’s really comfortable. We’ll have lighting in there, we’re going to put shade fabric in so it’s nicer in the summer. We’ll put in passion fruit and grape vines to shade it out, make it more comfortable in the heat of the summer. We plan on putting edgy plants in there, like fig trees, and keep producing a wider variety of crops to show how to do it, and also just to make it feel really good. We’ll take our landscaping backgrounds and make a beautiful, inviting space.

Mary [Emmett] has been working with the land and cultivating food for the community for over four decades now, [at Plymouth Orchard and Cider Mill]. Here at Gateway, she wanted to provide nutrient dense food to the community. Really what she was looking for was creating a space that felt like sanctuary, a space for horticultural therapy, trying a different approach, a kind of future-of-farming approach.

The first time we met, we’d pulled together this presentation and we were pretty excited to meet this client who wanted to do something that’s totally up our alley--putting in ponds and perennial food systems and wildlife and native plant areas. And somewhere in the meeting she looked at me and said, ‘You know, I’ve been waiting a really long time for you to show up.’ That felt good. Charlie and I, both of us have gone through a variety of careers and paths as we’ve gotten to the point where we are today. All of that has informed what we do. It’s unusual, it’s different, and it’s not for everybody, but the people that can recognize it, someone like Mary Emmett, who was looking for a different approach, she was very excited to find and meet us and have us jump on board.”

“The great thing about having a patron like that,” said Dr. Brennan, “Who trusts us so much, is that we get to express what things can be done and we take it further. We experiment. We push the edges a bit, and you come up with landscapes like Gateway Farm.”

“Mary is an experienced farmer,” continues O’Brien. “She’s been doing this for a long time, and so she knows what it takes, and she knows the kind of resources that are needed to be efficient and be edgy and try things out and produce something really interesting that the community’s going to want to see. She also makes our jobs easier by making sure we have the resources we need to do the work. She knows the value of that, and that’s part of the joy of working for her. Her willingness to invest into these types of things, not only for the people that work here, and our growing and our learning, but also for the whole community.

What we’ve been working toward here is soil health, water health, and human health--how they’re directly related and the importance of that. It’s a collaborative effort. It takes a lot of people and a really dedicated team to make this project happen. Luckily, we have those people in the project and it’s growing because of that. If there wasn’t a big team doing this and dedicated to it, we wouldn’t be here today. A lot of people take on permaculture as homesteaders and think their family of two or five are going to take care of acres of land, and they find that’s really challenging. Charlie and I, part of our mission is to kind of debunk the myths of permaculture so people can be successful. When you look at a farm like this, we have fifteen to eighteen people working here during the height of the season, it’s a reality check. You’re not going to take care of thirteen acres this intensely as a family of two laborers. This is a big group effort—all farms of this size are.

We had a few tours at Gateway last year, and having the community come in and ask questions and start to engage with the property through our workshops and the tours was really fun to see. I think we’re ready. The whole team’s really ready to open up the gates and say, ‘Come and enjoy this thing that we love, that we’re passionate about and dedicated to, and working really hard to maintain and care for.’ It’s been a leap to get to this place. It’s been a lot of work for everybody, but we’re really looking forward to it.”

Learn more about the farm online at gatewayfarmplymouth.com or visit them in person at 10665 Joy Road, Plymouth, MI. You can also give them a call at (810) 354-5154 or email info@gatewayfarmplymouth.com.

The buzz had been building for months about White Lotus Farms opening a Café, and by the time you’re reading this, it is open.