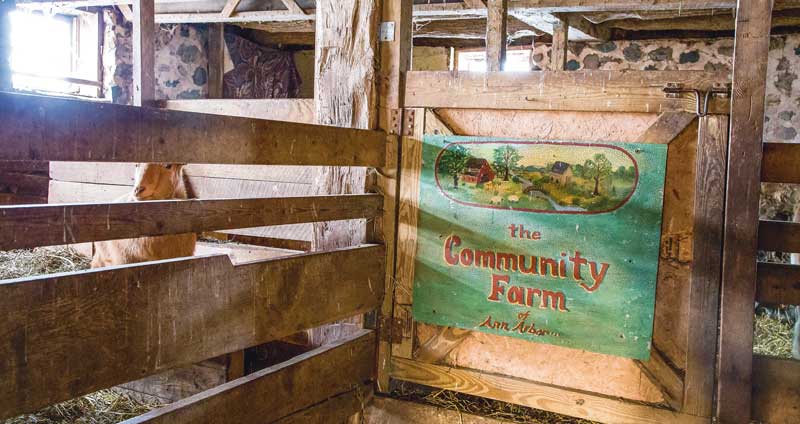

Ann Arbor's Most Beloved Countercultural Couple, Annie Elder and Paul Bantle, Prepare to Pass On Their Stewardship of The Community Farm

By Sandor Slomovits | Photography by Fresh Coast Photography

The 2017 planting, growing, and harvesting season will be Annie Elder and Paul Bantle’s last at the Community Farm of Ann Arbor. The two have been the head farmers tending the land and the animals there for more than 25 years. Even before they began working at the Farm, they were deeply entwined with the Ann Arbor community through their associations with the Wildflour Community Bakery, the Soy Plant, and Eden’s Restaurant (all three were natural food establishments of the seventies and eighties). But early in 2018 the couple will be moving to California to start the next phase of their lives.

Aptly enough, on the morning of November 8, 2016—talk about big changes—Paul, Annie, and I sat in the greenhouse on the Farm and talked about how they came to be at the Farm, what it has been like to care for it for over a quarter century, who will take over, what will change once they leave, and what’s in their future.

Annie and Paul both have ruddy, weathered faces, attesting to their many years of outdoor work. Annie has long silver hair, while Paul sports a full beard and often wears a hat. I have known them for many years and have always found them to be exuberantly cheerful, welcoming, and enthusiastic. Their language is colorful, dramatic, vibrant, often almost poetic, and our conversation was frequently interrupted by joyous laughter. While we talked I found myself wishing I could supplement this article with a video of our conversation. They clearly respect and enjoy each other enormously, listening intently while the other one speaks, often chiming in with affectionate, generous praise or agreement. When I start by asking them to tell me about their childhood and families, Paul says, “Why don’t you kick it off, dear one?” and Annie does—surprising me by beginning with Paul’s story, rather than her own.

“Their language is colorful, dramatic, vibrant, often almost poetic, and our conversation was frequently interrupted by joyous laughter.”

“Pauli was raised in Adrian, Michigan, and his family ran Lenawee Hills Greenhouse and Nursery.” Born in 1955, Paul was the sixth of seven children. “The seven children were always a hope, I think, to their parents to continue the business,” continues Annie, “And the seven children, as fast and far away as they could go, moved. So, none of them took over the business.” Nevertheless, Paul was surrounded by plants and by growing things throughout his childhood. While he was still a young boy, his mother suffered a heart attack that weakened her, and Paul became her main support. “It was a lovely thing,” says Annie, “I think mutually. She really enjoyed having Paul as her helper, and he learned very loving, tender, domestic things from her.”

Paul attended the University of Michigan, intending to become a medical doctor, graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in zoology, and then joined the Peace Corps for two years in Korea. He worked with a traveling nurse caring for people, particularly tuberculosis patients, in rural villages in the mountains. He stayed in Asia for two years after his Peace Corps stint, “Wandering, vagabond style,” adds Paul, picking up his story. “I was almost all the time outdoors, even nighttime. I walked everywhere up in the mountains and along the coasts, all over India, Thailand, Burma, Philippines, Nepal. What Asia did for me was crystallize my spiritual pursuit, and crystallized my relationship to nature and food and how that could be a basic vehicle for service.”

Paul shifts the focus. “Annie was born in 1956, and she likes to tell folks that she was conceived in Alaska, and that there were even some moose involved.” (Delighted, prolonged laughter and we move on.) Growing up in New Jersey, Annie was the oldest of six children and, like Paul, she was her mother’s main assistant, in her case helping to raise her younger siblings. Her father was a biology teacher in the local high school, and the family was politically very progressive, particularly around issues of race. In her teens Annie started working “across the tracks” at an after school program for African American kids. “Our family encouraged us to not even think about color. We had three heroes that my parents taught us: Gandhi, Jesus Christ, and Martin Luther King. So we just followed those teachings, and when I worked there, it wasn’t like, ‘Here are these poor black children and me,’ it was just, ‘Here’s some kids that need some help and want to have some fun.’”

Paul chimes in, “I think that was a pretty amazing thing, that during that period, in the early 1970s, when people were trying to figure out how to dissolve the race barrier, you were just doing it. You were just living it naturally. Anyways, you got off to a good start.”

Annie teases Paul, “You talked a lot more about me than I got to talk about you.” Paul laughs, “OK, let’s move on to the next topic.”

They met at Ann Arbor’s Wildflour Bakery in 1984 after Paul returned from his travels in Asia. Annie was working there, having moved from New Jersey earlier. “We actually were in Ann Arbor together before that because I was in school here from ‘73 to ’78,” says Paul. “We could have been in Mr. Flood’s Party at the same time!” adds Annie dramatically, referencing a favorite 1970s downtown music bar and hangout.

“I got back to this country, and the only thing I knew was I needed to go to the People’s Food Co-op, because I knew there would be like-minded people there.”

Paul goes on:

I got back to this country, and the only thing I knew was I needed to go to the People’s Food Co-op, because I knew there would be like-minded people there. And lo and behold there is the Bakery right next door to the Co-op. I walked into the Bakery and this woman comes bounding up to the goodie case, with a gorgeous smile and just radiant! I bought a goodie and I thought, ‘Wow, this woman is something else!’ This was fall, winter was coming, she had boots on, and I said to her, ‘Winter is coming and I don’t have the proper footwear. What would you recommend?’ And she told me that I should get some Sorrels. And I said, ‘OK’ and that’s what I went and bought, and indeed that was a very good choice. (Laughter.) Not to mention the goodie was pretty good too. (More laughter.)

“So Paul came into the Bakery and he would volunteer,” continues Annie.

“Always on her shift,” interrupts Paul, and Annie giggles.

“He was a wonderful, wonderful volunteer, always clear, always kind, very thorough, willing to do anything all the time, just the ideal worker. I just could feel there was something pretty special about that fellow. And the more I worked with him the more apparent that was.

Paul gradually went from volunteering to working at the Bakery. “He continued to just be amazing. He’s very skilled at peacemaking, being very, very fair. Paul was always just this wise, kind person, helping work out all the conflicts that would come along, and celebrating. So, of course, he was the fond guy of many of the gals that worked in the bakery.”

“Oh really!” asks Paul. (Laughter.)

“Yes,” says Annie emphatically.

“You didn’t tell me back then!”

“Well.” (Laughter.)

“Could have changed the course of life,” says Paul, laughing. “No, I think it worked out good, didn’t it?”

“So in the end, we decided that we would come together,” says Annie. ”Slowly we unveiled our fondness for each other.”

“It was rough sometimes, too,” says Paul.

“Yes,” agrees Annie. “The beginning was very rough.”

Paul explains:

She was a single mother with Mahogany when I came onto the scene. As a young fellow travelling, I had daily rhythms, I always woke with the sun and went to bed with the sun, I was pretty regular that way. But to come into a home and learn from Annie how to be in a home and be with a child growing up was a wonderful undertaking. And she was much better equipped in that regard than I was. So I learned a lot. You’ve got one girl in the family, Mahogany, who is still very in love and attached to her father, and you’ve got this kind of interloper coming in. That takes a lot of years to settle into a loving family. It took five years of working together in a collective setting, the Bakery. It was a great training ground for a long-term relationship, for making a household.

Finally, on a family camping trip in Washington State, they hiked up a mountain and found a hot spring. “There’s nobody around,” says Annie, “So, of course, without our clothes, we sat in the tub, talked about life and love and commitment, decided that we would be monogamous, and kind, and loving to each other, and serve our community together. That was the full moon of August 1989, and we consider that our wedding.”

“That was essentially our vows,” says Paul, “That our relationship would be grounded in being of good service in our community. There were clearly other aspects to it that were very passionate and moving through all the years, but I think that’s what we’ve returned to over and over again.”

Annie and Paul became farmers after Cindy Olivas, one of the bakers at Wildflour, along with her partner, Marcia Barton, helped found the Community Farm of Ann Arbor. Olivas and Barton had studied biodynamic farming in Kimberton, Pennsylvania, and brought Trauger Groh to Ann Arbor to talk about CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture). Groh, a German farmer steeped in the biodynamic agriculture ideas of Rudolf Steiner, helped bring those ideas and practices to the United States in the mid-1980s.

Olivas and Barton began running the Community Farm in 1988, and in 1991 they asked Annie and Paul to take over for them. Annie and Paul had long been associated with Ken and Cathy King at Frog Holler Farm, Paul having worked there as early as 1978, “They were like mentors to us,” says Annie. In the spring of 1992 they became the head farmers at the Community Farm. “In our 25 years on this farm, we’ve watched children be born, grow up on this food, and then come back as workers. We’ve been so intimate with so many people for so long.”

And now they are planning to move on. The whole time they have been farming, and even for several years before, they have been practicing a form of meditation called Passage Meditation. In 2018, they plan to move to northern California, to Tomales. There, on the coast in Marin County, is a residential community of people who have also been practicing Passage Meditation, and is where the organization’s headquarters and retreat center is located. “We both already have roles that are quite nice, and we can be occupied there on a full-time basis,” says Paul. He has been leading meditation retreats throughout the country for years and will continue to do that there, while Annie will help with preparing food, taking care of some of the elders of the community, and gardening. But, Paul hastens to add, “It’s a garden, not a four acre farm.”

Annie: Something that I really aspire to do, in the words of Dick Siegel, [popular Ann Arbor songwriter] is to ‘walk a little softer on this earth.’ I feel we’ve done really good. We’re conscious of our carbon footprint and we’re trying to bring as much local agriculture to our area [as we can] and raise consciousness in that area, but I still think there’s something more I can do. The changes that I feel we need to make, and I need to make, are changes in ourselves, in myself. And those are changes like becoming less self-oriented and really putting others first in all of my choices: not only people, but also the planet, in everything I do. Also, really slowing down. I don’t drive a car but I can still slow down my mind. I think that’s really important. [These are among some of the basic tenets of the Passage Meditation path that Annie and Paul practice.] I always hope that what I do can somehow inspire others to do. That’s what I’m hoping for from me in this move.

Paul: We’re trying to find that next stage of inner growth. It’s not that we couldn’t find it here too. This is a beautiful context for that. The whole biodynamic agricultural stream is founded on spiritual discipline. Rudolf Steiner suggested to the farmers in his agricultural lectures that they become meditators, and so we were really fortunate to be able to meld this path with the biodynamic farming pursuit. But now we’re at this threshold where I think if we kept going in the fashion that we’ve been going, we would be exploiting our bodies. We’ve already probably taken it over the edge on that (laughter), and it’s our instrument for our spiritual development, and for our service. We have a lot of service left in us. And if we just use that body up without paying attention, it’s not a smart way to go. This offers us another opportunity.

But they’re finding it difficult to find people to take over for them—for a variety of complex reasons. The Farm was only the eighth CSA in the US and the first in Michigan, but the movement has grown tremendously since those early days in the mid-1980s. There are now thousands of CSAs throughout the country and they have morphed and changed in many ways over the years, but the Community Farm is still run in the original CSA form. The members own all the assets of the farm—the cow, the equipment, the land—and the farmers do not own anything. They have no personal equity in it.

Paul: We’re still out of that classical mold, and it’s made it difficult in some ways for us to survive in the modern day context, because all these other CSAs offer a kind of convenience that makes them very attractive. We kind of have to hustle a lot, and educate, and show people why they would want to be a part of this.

The other thing is, almost thirty years have passed since the founding of the Farm and we’re confronting new issues, new obstacles. One of the things about the whole CSA movement in the beginning was that family farms were failing because the next generation didn’t want to take it up. They were going to universities, to urban areas; CSAs were going to be the ready-made vehicles for handing it off. Well, here we are, we’re aged farmers, now it’s the test of the experiment. And I think there must be other farms in the country that are the same age group, that are confronting the same thing.

One of the earlier issues was land tenure: how these farms were going to secure the land they were farming. Many of them had to address that, and many of them did it through land trusts, and many of them established non-profit educational arms, like we have. But now it’s the people issue. What do you do with aging farmers, who can’t crawl around on the ground as easily, but the pension outlook isn’t like a corporate outlook.

Annie: Our situation is tricky because if we were traditional farmers and we owned our land and assets and we had children that didn’t want to take it up, we’d sell those and that would be our pension. But we don’t own the land, the equipment, we don’t have a pension.

Paul: We’ve got to find this new clan of farmers. We’ve got this organism that’s been so driven by this centralized passion and work ethic. How are we going to find the right people, and find an economy that supports them, and keep the vitality of the organization going?

Annie: That’s our conundrum. We’re looking for people to take our place but not to do what we do. And that’s partly why we have to leave, because the farm has to also shift. What it has been doing for 28 years so beautifully doesn’t really fit society right now. Society has changed in all this time. So the farm has to take on maybe a new look, make some changes. But we are old school, and the ideas that we keep thinking are sort of new really aren’t; they’re still that same form, so if we step out our hope is that new blood, new ideas, new youth will come in to take our place and that will keep the farm going.

“The members own all the assets of the farm—the cow, the equipment, the land—and the farmers do not own anything. They have no personal equity in it.”

Paul: We keep knitting it together through our will forces, which are strong. The food’s good, the way of life is good, and our passion is good. So we can keep figuring out ways to thread the economy together to support it and we’re frugal in our own personal life, but that’s not a construct that will carry the farm forward. It’s too oriented around us at the center, pulling all those threads. And we’re getting worn out doing that. It’s not sustainable for us either.

Annie: For me…you get to be outside, and smell the air, and watch the sun and the clouds. You get to watch the plants grow, you get to tend the animals, you get to see these children grow more healthy because they’re eating this food. Wow! Anyone would want this job! [Her voice drops to a whisper.] We’re not finding that.

When we first started farming, we hired co-workers. Some were our age, but a lot of them were a little younger. Then, after a few years, as we were hiring the same age people, we realized, ‘Wow, we’re as old as their parents!’ And now, in the last couple of years, we’ve realized we’re as old as their grandparents! (Laughter.) It’s so wild.

Paul: The fun thing is we get along really well with them. It just feels like we’re not that different. We know we’re different from them, but we don’t feel that different too. They keep us vibrant and vital. Their pay, relative to what other young people are making at entry-level jobs, they are not making money. So they come to it for the sake of what it is. They’re passionate. But it’s another level then to take on the totality of running it [the farm] and being with the animals day in and day out.

We’ve heard this from many young people now; I think they’ve watched their parents and grandparents do what we’ve done, and they don’t want to give their all to one thing. They want a more balanced lifestyle. They want to be able to have time to go to the lake and canoe and swim, explore friendships. I think there was a period, maybe in the 60s and 70s—and I’m guessing this—people got so passionate, almost driven, about the causes they were engaged in, that that’s where they principally got nourished. My sense is this generation has watched that and they want to be nourished in lots of different ways. So it might take a combination of people to run it. I think it could take years for this transformation to get to a good solid position.

Another of the issues facing the Community Farm’s transition is its structure, where the farmers, members, and board of directors need to work together on decisions affecting the farm. Paul and Annie have decades of experience in leading and working in collective communities, first through their work at Wildflour Bakery and then in their years on the Farm, helping to lead in a manner that manages to include and involve everyone in a diverse group of people. They speculate that whoever takes over after them will need to be a leader who has, as Paul says,

That ability to include all different kinds of people. This is why we thought that if a core group [of the members of the Farm] meets, and it’s small—because many people have been with the Farm for twenty years or more, and they’re not interested in coming to meetings any more so much—they won’t be represented in that process necessarily very strongly, unless the people that are present there recognize there is all these different types of people, and figure out how to draw them out and really represent their perspectives in evolving the farm forward. That’s a big thing. It’s consensus-based, not simple majority rule. Some people have come from the inside out, they’ve worked with us and they’ve got all the other stuff going on, but then they get into these meetings and they go…

Annie inserts, “‘You mean I can’t just go and do this?' Nope, you’ve got to check with the whole membership and they have to agree before you make that change. It’s a hard thing for people.”

Paul: So even that may have to adjust itself somehow.

Annie: The farm needs to shift to be sustainable. And if we’re here, without meaning to, we could stop that shift.

Paul: We occupy a lot of space. (Laughter.) It’s hard for us not to. It’s a great dance to learn to recede into the woodwork a bit to create the proper space and vacuum for others to enter into, but also to be present to support that process and use your intelligence that you’ve developed over time, because they’re calling for that too. We’re learning a lot about detachment in this process, but we also have a responsibility to the cow and the animals—they’re living beings that are counting on us. We make sure they’re taken care of.

Annie: This farm uses biodynamic agriculture; it really tries to incorporate the spirit of the earth itself as our mother, and the spirit of the sky above, the cosmos and all those forces, all those influences. The people that dwell on the farm, the people that work it on the earth and the cosmos, it all comes together with love.

Whatever comes into the future of the farm, love will be its center, like it has been for all these years.

Paul: Down through the ages, brilliant beings that have come and gone, including Rudolf Steiner, they’re all trying to help us see that there’s an unseen world, they’re helping us get a glimpse of an unseen world that they can see. This farm is predicated on that whole journey of seeing more and more of the unseen and developing a relationship to it and trusting it and listening to it. It’s a living being, it’s a spiritual entity now and radiates all around and threads into our community of creatures and plant life and people. It really is much more than its material incarnation, its physical body. And that’s interesting at this time because the attachment part of me says, ‘Don’t let that go.’ There’s a part of me that just wants to hold on to this form and have it last forever. And then there’s the detached part that I’m trying to learn about that says there’s an impulse here that’s way more vast than I know about, and it’s love—it’s what Annie said about love—and I don’t get to say how that’s going to take its new form.

Annie: This community, the life that we overlap with here, has filled my being, my heart, and my soul. It’s in my dreams, and to let it go is a lot like dying to me. We’re so, so lucky because we have a spiritual practice. Thanks to our practice and to Paul, who’s often been taken by this subject, I have been able to embrace death in a much easier way.

With tears filling her eyes, Annie says, “We’ll miss this place.”

****

I checked in with Paul and Annie again in mid-February to ask how things were progressing with the transition. I had gone to a membership meeting in December and then also heard at several other meetings in the last few months, the Farm’s membership had gotten clearer on the qualifications for Annie and Paul’s replacement(s). Annie confirmed this,

We’ve restarted the search and we’ve got a number of beautiful applicants. They’re young, they’re green, they’re new at it, but they have enthusiasm and creativity, and I think what’s going to happen is just what we need to have happen. The farm will turn over to a stream of young, vibrant health.

We then continued to talk more about the unique qualities of the Farm.

Paul: I think in our earlier conversations with you we talked about the farm being a healing center. In the last few years, as we’ve been on the farm longer and longer, that’s what we’ve recognized it to be. You know in the early 1900s, or maybe the late 1800s, there were a lot of farms that were essentially hospitals. They closed many of them down, they turned them into other things. People that were quite ill or mentally imbalanced, however one says that, would go to these farms that served as therapeutic centers. Then I don’t know what happened, but they evolved away from that. I actually think that that’s what’s going on now, not just with our farm, but with farms all over this country and all over the world, at really healthy farms people are coming to get healed. I think in this age, where the world is in such a tumult, that at these farms people feel safe and secure, they quiet down.

Many people over the years have come from other countries, and they’re often very in touch in some way or another, they’re brilliant beings in their own fields, and they come to our farm and they bless the farm with their presence. A healer from the Andes came, a plum farmer from France, and this whole contingent from China. This last year a Filipino woman that wants to start collective farms in the south of the Philippines, and a woman from India who is doing…

Annie: Healing the earth from the Tsunami damage. She came.

Paul: Every year these people come. And they’re thrilled with the farm, but they’re brilliant beings and there’s something about their presence on the farm that takes it to a different place. It’s that kind of exchange that’s happened over all those years, I think, that’s saturated the spirit of the farm.

Annie: Education is an essential element of our farm and it starts with the members educating and sharing with each other, what to do with the vegetables, et cetera, so there’s a lot of communication that goes on within our membership because they come to the farm to get vegetables. That’s where our education starts.

Paul: That’s really probably our biggest offering in the community: on-farm experience for young people. I know that there are other farms that are oriented in that direction, but I think we’ve got a very well-developed program.

I recalled that I had brought my daughter here for a whole weekend some years back when her whole class from the Steiner School spent the weekend camping on the farm, participating in the farm’s activities. It was a wonderful experience, one we still talk about.

Annie: We have field trips that go from third grade up to U-M students that come out to the Farm. Our Farm doesn’t have any secrets. We are totally legal, totally aboveboard, totally open to anybody. So if people come and inquire, we share with them, because we want people to do good on the earth. If we have something that could help them, we want to share it with them. So people have come, even from other countries to learn from our farm. We welcome that. We love that. Competition is tricky but we don’t let that rule us. Really what’s important is that we look at the world all together.

Paul: Over the years we’ve always shared our planting calendars, our planting rhythms, all our seeds, seed sources, our bookkeeping, all our books are totally open to whoever would like to look at them. We’ve shared how someone new to the world of CSAs could form and operate their own CSA.

Annie: Sometimes when people ask, “What is the most special thing we grow?” We really do come back to love.

I ask Paul and Annie if they grow love. “We do, we really do,” replies Annie as she giggles with delight.

I suggest to Annie and Paul that that may be what is drawing all those people here, those who want to offer something, as well as those in need of healing, maybe even whether or not they know it.

Building on this, Annie explains:

The essence of biodynamic agriculture, which is the farming practice that we use, recognizes that the earth is a living, breathing being and that we need to be gentle to her and help heal her and give gratitude when she supplies us with this wonderful food. That’s been an important part of our farming practice and I think people can feel that even without talking to us.

Paul responds, “Yes, it just goes around and around and around.” (He chuckles with delight.)

To learn more about the Community Farm of Ann Arbor, Annie Elder, and Paul Bantle, and for information on their search for new farmers, please visit communityfarmofaa.wordpress.com/ .