Juliet Seignious is a local artist, painter, and dancer.

Story and Photos by Hilary Nichols

With a shared sigh, the two of us silently reach out to hold hands across the dinner table. We sit like this for a long moment, eyes closed with our hands clasped over the salad bowl and bread board, lost in the gentle impact of such a heartfelt expression. Conversations with Juliet Seignious often invoke that exalted experience that I can only describe as a soul connection.

Seignious is a fine art painter, sculptor, collage artist, and a dancer. She has been serious about her art ever since she was a young child in Harlem, keeping busy with her paintings on rainy days. But it was her dancing that she devoted much of her professional life, since attending the High School for Performing Arts, well known for its depiction in the movie Fame. In 1961, while she was still apprenticing at the American School of Ballet, as the first African American to be offered the coveted spot, she joined Alvin Ailey’s Dance theater of Harlem as a founding member. In 1978 she opened a dance studio in the Hudson Valley, in upstate New York, and it was there that her painting career took on more prominence, crafting a body of work that she sold at art fairs throughout the United States. In 2016 she moved to Ann Arbor to join her son, a professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan.

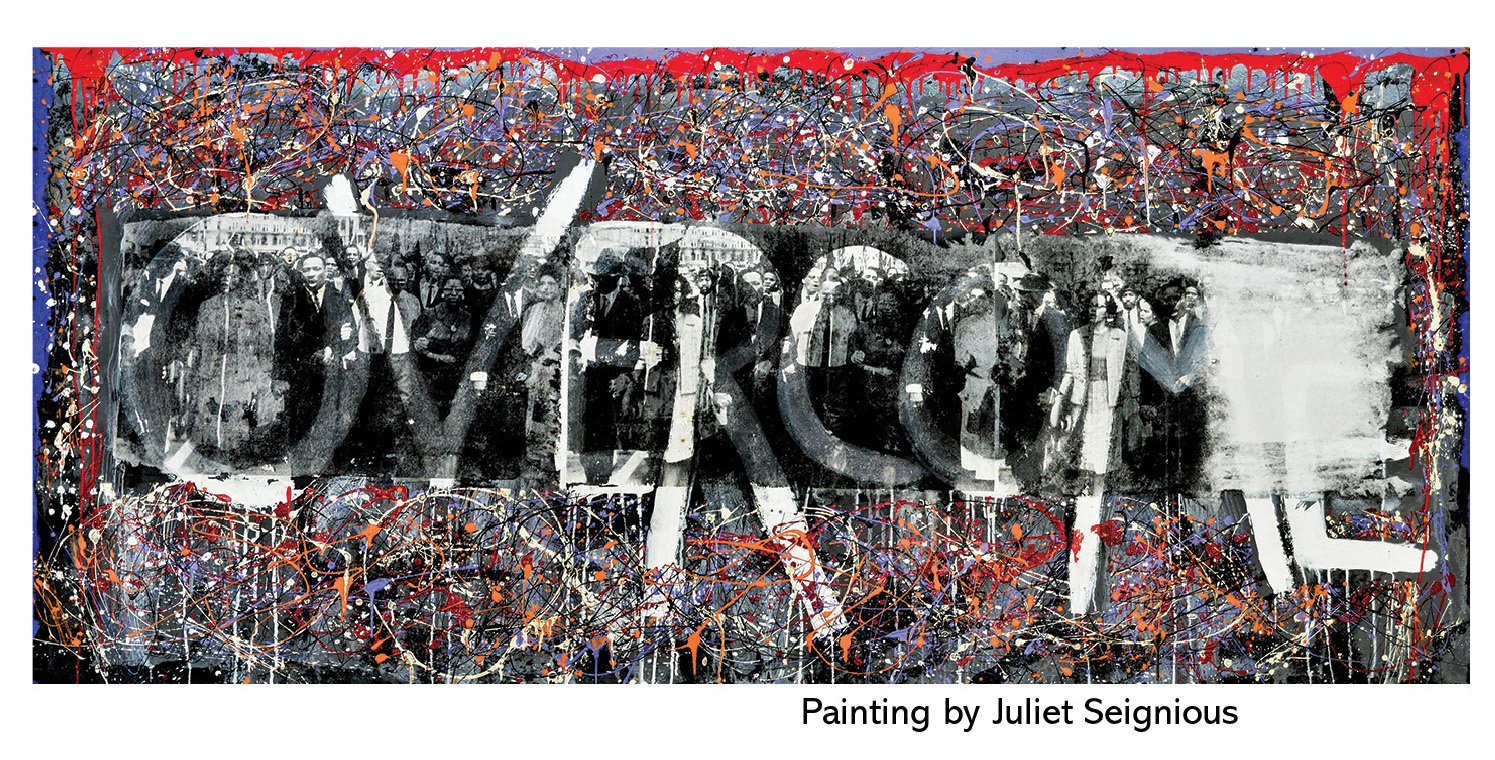

Into her attached basement apartment in the Barton Hills area, she transported her paints, canvases, and rolls and rolls of her works, on her signature heavy duty tar paper. The surface is durable and rich in metaphor, for a poignant piece aptly titled Family Tree. The three feet by six feet pieces stretch along the wall, layered with bright paints, layers of cheesecloth, shells, and stories. When the splashes of red, blue, purple, violet, and orange paint dry, she transfers an appliqued image of the March on Selma, and then in opaque white, layered over the imagery, she letters the word “overcome.” Her piece on Olympian Jesse Owens was exhibited at the Charles Wright African American Museum just weeks after her arrival in Michigan. Seignious is not afraid to make a statement.

At the beginning of the pandemic, she committed to making a piece a day. This series of smaller paintings, titled Abstract Journey is reaching over 283 images collected. It was by accident that became unified when her abstractions were interpreted by a friend who commented, “The darker shapes look like coffins.” With surprise, Juliet agreed, and the theme took on deeper resonance, as it correlated with the history that was heavy on her heart. “Within the abstract work, the meaning was made clear. The coffins represent the slaves buried beneath Wall Street in New York City, and the simple figures on the horizon are the spirits that carry us forward.” Art and activism are aligned for Seignious. The act is one in the same, but it is the spirit that inspires.

It was in 1973 that Seignious read a book that she credits as the catalyst to her spiritual journey. The book The Infinite Way by Joel Goldsmith opened her up to a perspective that has remained central to her being. “The road to having no judgment is a long and difficult one. It means sacrificing things, giving up a sense of separation, opening your heart again to feel that oneness. It is a practice, pretty much every day.”

And it is a practice that Seignious applies every day. “The empty surface provokes me, and then I hear the voice, ‘Just put some darn paint on the canvas!’ From there I let the colors and brushes take over, without judgment.”

She continues to exhibit her works to inspire others to create, to keep close to spirit. “This comes under the heading of love, self-love, opening up, for that love to come through.” Whether viewing her showings at WSG in Ann Arbor, at the Charles Wright Museum, Riverside Art Center, or in her home studio, it is undeniable, you can feel her passion palpably. When I ask her my signature question, how is she living her convictions, she muses, “It is the same with my dancing. I seek to be in the zone, and the audience feels that. That is what matters most.” And it becomes clear that there is not much of a distinction for her between her styles of art making. For Juliet Seignious, painting is a kind of dance.

Currently Seignious is collaborating with her grandson as her co-author on a children’s book titled, Tut, The Giant. You can learn more about Juliet Seignious and her artwork on her instagram account @julietseignious.

Will Sherry is the director of Strategic Initiatives for Student Life at the University of Michigan and the former Director of the Spectrum Center.

The University of Michigan is lucky to have Will Sherry in the LGBTQ+ conversation. Without a doubt Sherry has both influenced and been influenced by this decade’s LGBTQ cultural shifts. Now, as the new Director of Strategic Initiatives for Student Life, and while directing the Spectrum Center for 14 years, Sherry has been at the table. The center has been a foundational part of U-M’s campus culture, with a strong hand in earning a five out of five-star reception on the Campus Pride Index.

It was in 2007 as a graduate student in the School of Social Work that Sherry first volunteered there. “The rainbow network in the School of Social Work introduced me to the Spectrum Center and other places to gather with kindred people.” In 1971, when Jim Toy pioneered the Center, the achievement was monumental, as the first office for queer students in an institution of higher learning in the United States. Both Sherry and the center have changed a lot since this early introduction. “The Spectrum Center has really grown. I was the fourth of a four person staff when I was hired. Two directors and two program directors, along with a few students. It was rough in terms of budget. Our programing and operations budget was $5,000 to $10,000 a year, for all speakers and programs. Now there are six full time staff with program specialists and 10-15 student staff each year.”

The Center now has education, advocacy, and community building programs all over campus and all around the calendar to enhance the campus climate for LGBTQ+ students, staff, and faculty. In his new position Sherry has advanced that effort to develop programs that provide diversity, equity, and inclusion for all the underrepresented populations on campus. While Sherry carefully crafted programs to offer the most nuanced and strategic support, he was taking his own journey of self-reflection. Will Sherry uses “he, him, and his” pronouns, but that wasn’t always the case. “I identify my sexuality as queer. That’s a word that I feel like really represents the way I see gender. I identify as a man, and I also identify as transgender.” As part of the Bentley Historical Library Oral History project Sherry continued, “I identify as a parent, and as a partner, as a social worker. I identify as white, and lots of other things.”

Will Sherry is clear and careful with his language, and that is something that I really took note of. When I ask him about how he feels personally about pronouns and how the culture has advanced this conversation, he counters with “Offering our care isn’t really a vocabulary contest.” The language has changed and will continue to live and evolve with the population, but the important piece, it seems, is to be present for the care, rather than concerned about a slip up.

“Lots of people didn’t know much, about queer identity, but they weren’t queer.” When Sherry first arrived in Michigan for grad school, he wasn’t tapped into the community. In his upbringing, and undergraduate experience, he did not encounter a support system to celebrate his identity. In fact, when his housing search kept referring to LGBT, “I had never seen the term, like I didn’t know what it meant and didn’t know what it stood for.”

Graduate school offered Sherry a great shift in his awareness. It is on campus that many LGBTQ people are afforded the kind of life affirming and identity defining experiences that can be crucial for their long-term health and happiness.

Maybe that is why he is so great at crafting the programs that safeguards the well-being of students—because he is listening. He knows how formative this environment can be. “It was a real gift to come into the space. I really valued what people offered,” Sherry realized. It was those offerings that informed his options when a friend mused, “Not everyone is comfortable in their gender.”

As a social worker, devoted to doing justice work, Sherry had to realize that some of that work could be personal. It was while working at the Spectrum Center that Sherry transitioned. In 2011, he married his wife, and they now raise their four children in Dexter, MI. He might not have always predicted this happy family story, but he always knew he would be a social worker. “I always knew that the job for me would have to be meaningful and impactful. I knew that if it didn’t align, it wouldn’t be of interest for me.”

Sherry spends his time in his new office at the renovated Ruthven center advocating for many clubs and activities. He offers campus wide DEI trainings, and campaigns for updated zoning that allows for more unisex bathrooms. All to keep pace with and progress the conversation, and ultimately to help all students on campus to find their fit, from Monday morning to Saturday night and all the rest of their days. Just as he has.

It was a passion flower that first stopped Susan McLeary in her tracks. The exotic flower ignited her passion and initiated her purpose toward becoming a florist, a designer, an artist, and an author. Yet, educator is the title Susan McLeary identifies with most these days.