By Michelle A. McLemore

December gave the world a lot to celebrate: Bodhi Day, Day of Our Lady Guadalupe, Hanukkah, Yule, Christmas, Kwanza, Zarathost Diso, and New Year’s Eve. Colorful lights and crackling fires against a crisp winter canvas always help me find time to ponder spiritual connections and how humanity has attempted to make sense of and, perhaps ironically, immortalize our understandings. The written word and art have always been equally powerful mediums for capturing abstract yet visceral emotions. Even tentatively opening the door to a museum or a used bookstore makes me catch my breath in anticipation and reverence for the sheer energetic power combined in one space from so many inspired, deeply affected souls.

I wonder as I wander the aisles: am I understanding what the creator intended as well as appreciating my own reactions? Art may be in the eye of the beholder; however, many artists infuse subtle messages—just as writers may use allusions. For the viewer or reader in the know, these hidden treasures become Easter egg goodies adding richness to the piece if recognized. For others, they are just benign, curious additions. And yet, what is the impact when multiple perspectives can be brought to the same piece for specific features? There may be either enlightenment or argument on which is “right.” And unless you are good with seances, asking the original artist’s intent may not always be possible.

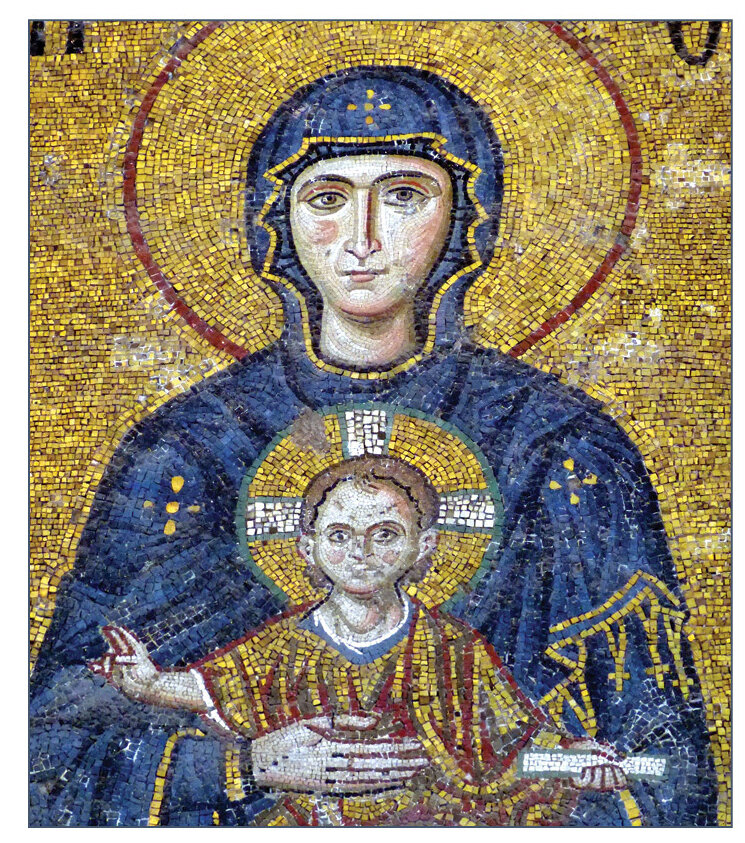

This recent season has led me to seek out spiritual art. In the midst of flowy angels, chubby cherubs, and aura shrouded mystics, I’ve stumbled upon diverse interpretations of artists’ intentions regarding identical hand positions used in a variety of world faiths and artwork from early civilizations.

When I was very young, hands and feet were difficult to draw realistically, so I’d inevitably “run out of space” on the page for the feet. Oops. I’d hide the hands behind hips or objects in order to focus on faces—the ultimate challenge in my mind. I’m certain if a seven-year-old can strategically position hands, then a master most certainly would not haphazardly throw them on the canvas. Hands add emotion for dancers, singers, mimes (sorry—I had to), in addition to general semantic meaning for the deaf or hard of hearing communities. Yet, gestures have also had specific meanings for various groups which go beyond the common index finger pointing for “look there” and the middle finger for “you frustrate me.” Christian clergy, practitioners of Hindu mudras, palm readers, and professional Greco-Roman speakers—among many other peoples—all have specific meanings for very specific gestures used in art.

The question is…was there one original, influential basis for these hand positions, or as different cultures and faiths intermingled in the Mediterranean and Middle East did they influence each other? Is there a right answer for an art piece’s hand portrayal? Were there historical meanings that perhaps even the artists weren’t aware of when composing their piece?

Famous Roman orators, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE) and Marcus Fabius Quintilian (35-100 AD) both record that effective rhetorical delivery covers both enunciation as well as gesticulation of the hands—the latter coming to be called Chironomia. After much nudging, Quintilian published his rhetoric manual near the end of the first century CE. He mentions in The Institutio Oratoria, “No one will deny that such details form a part of the art of delivery, nor divorce delivery from oratory; there can be no justification for disdaining to learn what has got to be done, especially as chironomy, which, as the name shows, is the law of gesture, originated in heroic times… (189).

It makes sense that there would be common gestures for speakers and leaders to communicate across great crowds. For meaning to endure across centuries, gestures would have had to be recorded, taught, and used in a consistent manner even as a part of a commoner’s daily life. Religio Romano, Hellenistic paganism, Egyptian Heka, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Islam—all pre-Christian denominations—left evidence of gesture similarities in artwork. As time went on, these gestures also began showing up in Christian artwork and ceremonies—some still in use today.

Let’s examine just a few gestures—starting with a simple one—to add layers of perspective per chance you happen upon these gestures in the future.

The Point-er

First, envision pointing with the index finger and thumb toward the sky with the remaining three fingers pressed down to the palm, palm facing the audience. This was used to accompany a declaration, narration, offer caution, or request a pause for emphasis by ancient Roman orators. When I see it, the first image that comes to my mind is that of the Tinman in the Wizard of Oz when he says, “Someday they’ll erect a statue of me in this town.” Auntie Em interrupts, “Well, don’t start posing for it now.” His implied intention was to continue pontificating before Em reminded him to get back to work.

Now-a-days the meaning of the gesture hasn’t changed much. Teachers may use it to pause students’ discussion to make an additional point or add critical reminders. If you’ve seen the movie City Slickers, Curley informs that the secret of life is …and he raises his hand in this gesture. “One thing. Find it….” Oddly to the modern reader, for an ancient Roman signifying numbers by his fingers on the left hand, this gesture actually meant the number three, not one! (Romans could represent up to the number 10,000 using both hands and holding them at different elevations or locations (Bede the Venerable transcribed a list of ancient documents in De Temporum Ratione providing us with the proof.)

Continuing, in more literal artwork, pointing sideways or specifically at something has always implied, “Would you look at that!” (Yes, allusion to Ed Bassmaster intended.) Blatant pointing is seen often in classic paintings. The artists must have had severe doubts that viewers would be able to single out the key figures or action in a mural. Consider “Descent of Christ to the Limbo” in the Medici Chapel from 1522. In the bottom left corner, a male in earnest is pointing out the central descended Yeshua/Jesus figure to an unknown (to modern viewers) but probably “just” otherworld female.

In viewing “The Personification of Chastity”—one part of the Ascension cupola of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, Italy—the mosaic female holds her left hand up and uses this gesture: Is it to “declare” the virtue labeled next to her and in the scroll within her right hand? Are we sure she doesn’t mean the number three? We would need to view the figures around her to see if perhaps there is a line of virtues and if she is in the third position. She certainly is not pointing to draw our attention elsewhere as her gaze is upon the label to her right which reads “Chastity” or “Purity” in Latin. The orator’s meaning of “Take note” seems the artist’s most likely intention.

The nineteenth-century sculpture of Protestant reformer Martin Luther, in Worms, Germany, uses this same gesture. The statue was to commemorate when Luther defended his thesis facing Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor in 1521. Luther most assuredly had a point to declare with a narration to accompany it. (You might note his left hand is held over his heart—another common gesture in the art world.)

Leonardo Da Vinci, however, put a twist on the gesture. In both, “St. John the Baptist” and “The Last Supper” he rotates the palm inward to the body. This changes the gesture to point upward with emphasis—“Look there, and note it is important.”

Not too complicated, right? Let’s add another: Grounding the Bird.

What happens when the middle finger is bent to touch the tip of the thumb? (The rest of the fingers point straight up.) Quintilian described this gesture use to indicate the exordium—the actual attention-getting part of a speech. Memories from English class may bring back options of anecdotal narratives, imagery, or a relevant quotation by someone famous. The goal of every intro is to hook listeners—to bring them to the theme through personal association and understanding. How would that look in artwork? Often artists who included this right-handed gesture also composed something symbolic in the left hand. The two would work together to trigger a concept or memory in the viewer.

Examining the central figure of Yeshua/Jesus in the scene of the Deisis at the Vatopedi Holy Monastery, he holds this gesture with his right while the left hand holds pages of the Gospel stating: “I am the light of the world, the truth, the life, the resurrection, the way, the Shepherd, The Door: /through me if one enters in, he will be saved.” They are compilations of John 8:12, 10:9, 10:11, 11:25, and 14:6. The scene is a mosaic above the entrance to the narthex. (Per Google, between the third and fourth century, a narthex is a meeting area on the western entrance of a church for those not allowed to enter the main worship area but who still want to hear the sermon.) So, imagine, one who is not worthy-enough to join the main congregation, but is a seeker, sees this image while physically entering through to the area to be enlightened; the declaration is all they must do is enter in, through, and with belief in this Holy Being.

Interestingly, when studying Hindu/Buddhist Mudras (hand positions), this same hand position is named Shuni Mudra or Akasha Mudra. Connecting the energy of the middle finger and thumb is believed to nurture understanding, kindness, and patience toward others. Would a speaker be eliciting empathy in his or her introduction? Absolutely. If you cannot make a listener care about your issue, they will never agree with your position. And would speakers benefit from gaining patience toward their audience? Most certainly. Reading and relating to the audience is vital for an effective speaker to ad lib as necessary. The mudra additionally is said to promote living in the present moment—encouraging attentiveness to what one is hearing and seeing moment by moment—keeping listeners engaged. Finally, it is said to generate awareness of our inner divine self. Certainly, we could understand religious figures being painted with this hand gesture to symbolize their own divinity. Balance of the Yin and the Yang energies is a preferred state. But, in regard to oratory? Perhaps, to understand is truly Divine—a goal of all speakers and audiences.

Would Christians and artists know of the mudras in the twelfth century? Perhaps the real question is if Yeshua/Jesus and his subsequent followers would have known of mudras in their time? Hinduism is believed to be the oldest continuous religion dating between 8000 and 6000 BCE. Buddhism, it is said, originated in India around 400 BCE. Archaeologists have documented Buddhist gravestones dating between 305 BC to 30 BC in Alexandria, Egypt. Alexandria as a crossroads of trade and cultural interactions for Hellenistic Egypt could easily have transmitted awareness of mudras to many peoples and cultures during the development of Christianity. Additional interactions between Indians and various emerging Christian-type groups after the death of Jesus have also been documented in the Common Era.

Some Christians and Catholic clergy today attempt to shrug off the various gestures in religious paintings as all simply “blessings.” Yet, I question, why would artists bother creating different gestures if they did not have different meanings? (I can’t believe finger work in mosaics was that easy to do well.) It seems more likely—and yes, I’ll admit conspiratorial—that the knowledge was either lost or more likely suppressed so believers would not question faith origins. Still, anyone studying ancient cultures and literature easily observes how one culture borrowed and modified from prior ones in many aspects. It need not be a secret or threat if current beliefs are well-intentioned.

Ready to add another gesture and more perspectives? The Blessing.

A common hand gesture used in paintings and mosaics of Yeshua/Jesus, involves folding the ring and pinky fingers down to the palm while holding the thumb, index, and middle fingers straight up.

The gesture can be seen in the mosaic, “Christus Ravenna” or “Christ Surrounded by Angels and Saints” in the Basilica of Saint Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, dating to 526 CE. Additionally, it is used in Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” or “Savior of the World” dated between 1499 and 1510 CE. Da Vinci’s use is reported to be in the position of giving a blessing during the movement of the Sign of the Cross, though no one notes proof of that intended full gesticulation. His composition appears to be modeled after earlier Byzantine art pieces.

Egyptian Coptic Orthodox Christian Church clergy are still today taught that the first two fingers and the thumb represent the Holy Trinity—three in one divinity—which the church has defended since its founding by St. Mark, the Evangelist, in 42 CE. The two folded fingers represent the dual nature of the Messiah (human and divine). Therefore, a blessing done under this gesture is believed to hold the full power YHWH/Yahweh. It is used by Catholic clergy today as a general blessing.

And what of the pre-Christian/pre-Catholic era?

To Hindu followers, the same gesture is known as Ardhapataka Mudra. It emboldens people to free themselves from problems, vices, as well as physical, spiritual, or mental challenges. That meaning sounds like it would mesh well with a holy person giving a blessing—protection from all that would threaten their peace—as one sends his people back into the world. And then comes the next historical layer. Between 500 and 100 BCE a Hindu sage named Valmiki wrote a book on Palmistry (also known as Chiromancy) and its influence spread. A basic tenet outlined that each finger was assigned a particular planet.

In Mythology and the Seasons one article clarifies that the thumb represents Venus, the index finger Jupiter, middle finger Saturn, ring finger Apollo (the Sun), and the little finger Mercury. At the time of Valmiki, the Roman polytheistic religion and Greek counterparts were in full dominion from approximately 509 to 50 BCE. Looking at the Ardhapataka Mudra with the Greco-Roman deities, the mudra or blessing of protection is represented by Saturn, the Father (aka Chronus ) with the tallest middle finger, the son Jupiter (aka Zeus) as the index finger, and Venus (the feminine spirit) as the thumb. In Christian terms, Yeshua/Jesus, or second Divine incarnation, is between His parents or originators—the three in one Divine trilogy. Suddenly the Egyptian Coptic interpretation has a potential longer history of origin.

But wait, there’s more: Mano Pantea

This same gesture is found in even older times as a spiritual talisman of ancient Egyptians against “the Evil Eye.” Named Mano Pantea, Frederick Thomas Elworthy documented it and other talismans in the 1895 book, The Evil Eye: An Account of Ancient and Widespread Superstition. Built out of materials the average citizen could afford, it was believed to be set up in the home to ward off evil. The figure was adorned with multiple symbols directly related to Egyptian deities and concepts such as Isis, Osiris, scarabs, and protection for pregnant women and mothers. The fingers and thumb represented Isis, Osirus, and their child Horus. Again, we see a holy trinity of deities.

It was also interpreted as the Kemetic (Ancient Egyptian) sign for peace, blessing, and assistance. Some accounts record it was gestured by son Horus to father Osiris as he climbed the steep ladder to heaven.

But, Wait! Yes, going back even further, the hand sign has been found connected with Baal Hammon—a Phoenician weather and fertility of vegetation god—the King of all Gods. Examining the variety of objects used for protection in this gesture, one might question if the cultures were polytheistic (as long taught) or actually pantheistic. Pantheism.com defines pantheism as “the belief or awareness that God exists not as a separate, anthropomorphic deity, but as the Universe itself. And furthermore, that this intelligence and power and creative intent is inherent in all energy/matter.” Perhaps the Mano Pantea of ancient Phoenicia shows the people believed literally in the power of many natural creatures and elements and that these each could help protect one from envy or ill-intentions others might direct their way.

Hamsa Hand

An open right-hand gesture with palm facing outward, for orators, indicated the audience should cease talking—to stop coming at or trying to interrupt or challenge the speaker. It is called Abhaya Mudra by Hindi and Buddhists. It is used to offer divine protection from attacks of any nature and ward off fear of such attacks. From the hand radiates the faith, energy, and intention of the hand’s owner. These two meanings then coincide: Stop an unwanted advance. It can also be found in Tai Chi’s “Repulse the Monkey” sequence.

A toned-down interpretation, per Russianicon.com is the Russian Orthodox interpretation: the gesture “depict[s] a saint whose thoughts are pure and whose soul is open to the world… one of faith and truth.” Perhaps, the “of faith” part is the emphasis and the power coming from such enabling warding off trouble is downplayed?

In Arabic, symbolic hands are known as Khamsa or Hamsa. This same open hand, palm out gesture, named the Hamsa Hand, is actually used across many cultures. Scholars record evidence of the open palm protective symbol in amulets in early Mesopotamia and Egypt and on Buddhist statues. In Judaism it is called the Hand of Miriam (sister of Moses and Aaron). In Islam, it is called the Hand of Fatima (Mohammed’s daughter) (Elworthy, 355). For all, the intention was that it could ward away or shield the person from evil intent.

A stone stela of the open hand was even found in Carthage—a North African Phoenician civilization from 650 BCE to 146 BCE. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, sculptures, and paintings also use the extended right hand.

According to Amira El Azhary Sonbol in The Exotic: Women’s Histories in Islamic Societies (2005), the use of the Hamsa Hand was used so prevalently that in 1526 Episcopal Spanish clergy were pressured by Charles V to ban all open, right-hand amulets and encourage the wearing of crosses instead (Sonbol, 357). Jewelry and wall hangings abound today across the world with the Hamsa Hand as clear evidence in the continued faith in its protective abilities against evil or jealous intentions. Some households carry crosses as well as Hamsa hands.

The opposite gesture in form is the Varada Mudra—fingers pointing downward. In Buddhism, it is a gesture for giving gifts, boons, or charity. Likewise, as the Hand of Miriam or Hand of Fatima, it implies blessings if worn or displayed downward. Often, in spiritual artwork, holy figures are shown using both gestures simultaneously.

In Egyptian Coptic Orthodox training today, one hand up and one hand down deals with the binding and loosening in heaven and earth: In Jewish law, it references declaring what is forbidden and what is allowed. The protection and boon aspects are consistent.

Consider “The Wedding at Cana” by Isaac Fanous. Yeshua/Jesus holds his right hand down evincing his first miracle of changing water into wine as a gift upon his mother’s imploring while holding his left hand up in protection and blessing for the newlyweds.

The Ringer

A relaxed version of Ardhapataka Mudra is when the ring finger of the right hand touches the top of the thumb with the other fingers remaining straight. It is called Privthri (Earth) Mudra and is used to strengthen and heal the physical body. Connecting to the Earth, it is associated with the root chakra and when this gesture is held, it promotes a sense of groundedness and self-confidence.

In modern Catholic churches, a relaxed version is sometimes called the Hand of the Benediction. It is recognized as making the literal abbreviation of the name of Jesus Christ in Greek Orthodox iconography. The first and last letter of each word, from left to right is written as ICXC: the index finger pointing up, signifies “I”; the curved middle figure represents a C; the middle finger crossed by the thumb creates an “X,” and the pinky creates an additional “C.” When clergy say a blessing in the name of Jesus, they are attempting to literally do it through His name. Often in paintings and older mosaics, Yeshua/Jesus will be shown making this gesture as well as having the abbreviated name somewhere in the background nearby. Interestingly, you can see the traditional mudra form used in a mosaic of Yeshua in an orthodox chapel in Dromolaxia, Cyprus with the abbreviated name in the background.

Modify this gesture slightly again by touching the ring finger and little finger to the tip of the thumb and Prana Mudra is formed. In Yogic practice, it is believed to heal more than a hundred different kinds of diseases and health conditions by strengthening the immune system, promoting self-confidence, and increasing the body and mind’s resilience to heal itself. It’s interesting to contemplate spiritual leaders of various faiths shown using these mudras—especially ones known as great healers. Could Yeshua/Jesus have actually known the mudras and possibly taught it to the people he healed so they could continue in good health? The possibility takes nothing away from the stories of miraculous sudden healings. In my opinion, it takes the awe further to show His teachings were for both spiritual and physical health long term in humility by sharing world-wide healing strategies. Or perhaps, the artist knew the mudra and was simply adding that Easter egg layer to imply the healing powers of Jesus Christ?

These are just a few of several common hand gestures I’ve chanced upon in art across different religions, cultures, and time periods of the ancient worlds. The choices are intriguing, the possibilities moving.

An artist creates and releases its child into the world. He or she may publish notes on intent, but if not, intent is left to be interpreted, or sometimes crucified, by critics and viewers of every following age. It is a strong creator that gifts his creation without explanation and suffers through criticism, skepticism, or misunderstanding for all time. As Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “To be great is to be misunderstood.”

Michelle McLemore is a retired psychology and writing teacher enjoying a second life as a freelance writer, writing mentor, energy healer, and stress management coach. If you are interested in learning more about McLemore, you can email her at heartofthewalk@gmail.com. Interested in learning about more hand gestures through the ages? Look for a companion article coming soon in the CW Biweekly.

My son, an enthusiastic fan of classic cinema, once tried to convince my mother to let him watch a movie called Stalker before he went to bed. Being a sensible woman, she refused to allow her eight-year-old grandson to watch a film with such a foreboding title. He tried to explain to her that “stalker” in this context didn’t mean a dangerous and unwanted follower, but instead described a guide through a magical area called the Zone wherein lies a room that grants wishes. My poor mother again refused him as this explanation made little sense and sounded made up on the spot.